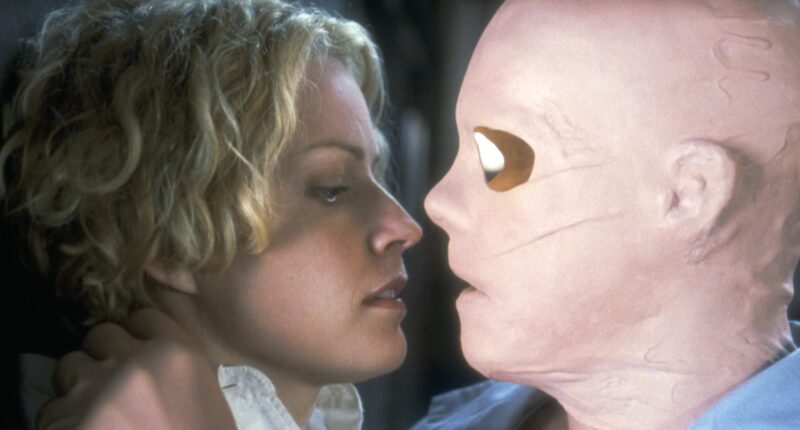

Even under the loose prosthetic skin that Caine at this point wears while invisible—a visual effect that remains impressive even today—we can tell that he’s smirking. Little does Carter know that Caine’s already done so much, including sexually assaulting his neighbor and spying on his fellow researcher Linda McKay (Elisabeth Shue), an ex-girlfriend now dating their colleague Matt Kensington (Josh Brolin).

To Hollow Man‘s original audiences in 2000, Carter’s attempted bromancing was just another example of Verhoeven’s cynical worldview. After all, the filmmaker had already given viewers a pro-fascist satire in Starship Troopers and a dark inversion of the American Dream with Showgirls. He excels at provoking audiences, and by 2000 Hollow Man‘s offenses felt empty and obvious. Yet today the specific nature of Caine’s crimes feel well-observed and all too accurate. Take one of the first things Caine does when invisible: he immediately sneaks out into the main observation lab where his colleague Sarah Kennedy (Kim Dickens) is sleeping. After confirming that she’s in a deep sleep, Caine unbuttons Kennedy’s blouse and begins fondling her.

Given how much the screenplay, written by Andrew W. Marlowe (who shares a “Story By” credit with Gary Scott Thompson), foregrounds the clashes between Caine and Kennedy, it’s clear that this is more than sexual leering on his part. He assaults her because she dared to challenge him, because he wants to exert his will over someone who tried to reject it. Most movies would keep such a blatantly disgusting act until later in the movie, so that we see tragedy in Caine’s downfall. But not Hollow Man. Verhoeven doesn’t see anything admirable in the character—or in anyone else onscreen.

A Visible Problem

When Caine first turns himself invisible, his colleagues gather around to celebrate. Although he can’t be seen, Caine certainly can be heard, as demonstrated by his constant boasting. “I see that the procedure hasn’t changed your personality,” snipes fellow researcher Janice (Mary Randle), delivering the line not so much with disgust but with grudging admiration. Janice’s feelings are hardly an anomaly. Even if Kennedy and Kensington clash with Caine, they always respect him. That’s even more true of Shue’s McKay, as the movie often finds ber grinning at Caine, revealing lingering feelings.

Moreover we believe that they would admire Caine precisely because Kevin Bacon’s so charismatic. Verhoeven takes full advantage of Bacon’s considerable charm, giving him plenty of space to smile and celebrate at his own achievements, and even to suggest that he’s harder on himself than he is on anyone else. But because this is a Verhoeven movie, it’s clear that Hollow Man never shares the character’s love of Caine. People around him love Caine for his hard work, his technological brilliance, and his boldness. But the movie, appropriately enough, sees right through him for the despicable person he is.

That ability to see the horrible person within boasting and success makes Hollow Man imperative today in a way it wasn’t a quarter of a century ago. Today we’re inundated with men whose boasts and success—whether it be the popularity of their podcast, the fact that they’ve become president, or simply their physical attributes—are met with uncritical adoration. These influencers and grifters point to that success to gain followers, who want to learn how to be just like them.