The colour flashed in front of my eyes,’ wrote Elsa Schiaparelli in 1937. ‘Bright, impossible, impudent, becoming, life-giving, like all the light and the birds and the fish in the world put together, a colour of China and Peru but not of the West – a shocking colour, pure and undiluted.’

So ‘shocking pink’ was born, a shade so vivid that no one in the 20th century had worn it before – but by then both flamboyance and originality had become Schiaparelli’s trademarks.

Next month, her work can be seen at the Schiaparelli: Fashion Becomes Art exhibition at the Victoria and Albert Museum in Kensington, London.

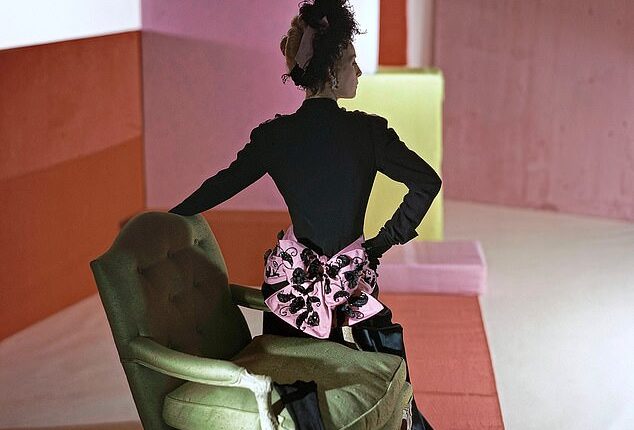

A Vogue model shot from 1947

On display will be the Skeleton Dress, its ‘bones’ moving as the wearer walked; also the Lobster Dress and many, many more of her ground-breaking, attention-grabbing creations. The exhibition will also feature the iconic bow-at-the-neck sweater that launched the designer’s career. For, along with her great rival Chanel, Schiaparelli (or ‘Schiap’, as everyone called her) was the most original and influential couturière of the 1920s and 30s. She was the first to show an evening dress with its own jacket; the first to make a feature of intarsia knitting (a motif, such as a collar, knitted into the fabric of a jersey); the first to display fastenings – zips, buttons and safety pins – externally, as ornamentation, instead of discreetly hiding them.

Schiaparelli’s clothes were like nothing seen before: brilliant embellished jackets, a twining serpent of sequins around a black sheath dress, a hat in the shape of an upside-down black shoe with high scarlet heel, gloves tipped with scarlet ‘fingernails’, an evening dress with trompe-l’oeil rips and tears, a suit with a jacket that looked like a chest of drawers.

Many resulted from inspiration taken from the artists of the day or collaboration with them: Picabia, Picasso, the polymathic Jean Cocteau and, most famously, Salvador Dalí, the best-known of the Surrealist artists. Schiaparelli’s collaboration with Dalí was not as surprising as it might seem, for as she had always claimed, ‘Dress designing is to me not a profession but an art.’

Zsa Zsa Gabor wears Schiaparelli in the 1952 film Moulin Rouge

The women who wore Schiaparelli’s clothes were often equally exotic. Take Daisy Fellowes (her second husband was the Hon. Reginald Fellowes), the half-French, half-American high-society heiress, and the first to wear the designer’s black suit with shocking pink lips for pockets. Sharp-tongued, spoilt and the epitome of 30s chic, for Fellowes outrageousness was a way of life. She enjoyed wrong-footing other women (there was nothing of the sisterhood about her) and would turn up in a simple linen shift when everyone else was dressed to the nines, or pair handfuls of emeralds from her fabulous jewellery collection with a bathing dress.

Above all, Fellowes was a voracious man-eater, ‘the destroyer of many a happy home’, as one ex-lover bitterly put it, who stole her daughters’ boyfriends and seduced her best friends’ husbands. Although she did not succeed with her future husband’s cousin Winston Churchill, plenty of other men fell under her spell.

Renowned party-giver and interior decorator Elsie de Wolfe (the wife of the diplomat Sir Charles Mendl), who was known for standing on her head for long periods of time and remained trim and fit at 70, was another faithful Schiaparelli client. So, too, were Diana Vreeland, who went on to become American Vogue’s editor-in-chief and famously declared, ‘Pink is the navy blue of India’; and the Vicomtesse Marie-Laure de Noailles, who, with her husband, championed the avant-garde.

Schiaparelli with Dalí, 1950

Another prominent fan, who deserted Chanel for Schiaparelli, was Nancy Cunard – tall, slender, with a cap of blonde hair and immense turquoise eyes invariably ringed with kohl (then barely known). This striking and glamorous young woman had left home, class and country to lead a life of hard drinking, poetry writing and constant love affairs in the seething intellectual and artistic surroundings of the 20s Left Bank in Paris.

From Hollywood came Marlene Dietrich, Katharine Hepburn and Greta Garbo. The voluptuous Mae West was a distant customer, sending not only all her measurements but a nude statuette of herself. The clothes ordered by the star were a lilac coat-dress worn with a purple hat, a bright cornflower-blue and green afternoon dress and an evening dress of black taffeta with pink taffeta roses, worn with a huge hat covered in enormous ostrich feathers.

But the most famous coupling of client and couture, perhaps, was Wallis Simpson and the Dalí-inspired Lobster Dress, to which American Vogue devoted eight pages shortly before Wallis’s marriage to the Duke of Windsor (the former King Edward VIII) in June 1937. This celebrated garment featured a huge Dalí-illustrated lobster, decorated with sprigs of parsley, splashed down the front of a white silk dress. It was said that the artist had to be dissuaded from putting real mayonnaise on it. (Wallis kept the dress as part of her trousseau.)

Mae West on screen in a Schiaparelli costume, 1937

Unlike most others in the world of couture, Schiaparelli came from an upper-class background. Where Chanel’s father was an itinerant street trader in the Auvergne, Schiaparelli’s was a distinguished scholar and Dean at the University of Rome, while her mother was a Neapolitan aristocrat who gave birth to the future fashion designer in a palazzo. Inventive and adventurous, she rebelled against the comfortable conformity of her parents’ life, first by going to Paris, then London.

Here, one evening, she went to a lecture on theosophy. Always impulsive, by the following morning she had agreed to marry the lecturer, Comte William de Wendt de Kerlor, a persuasive Swiss-born charlatan who claimed to be a psychologist, a phrenologist and a palm reader. After he was deported in 1916 for fortune-telling, which was then illegal, the couple left for France and then the US. There Schiaparelli acted as her husband’s assistant in his various scams, before he abandoned her shortly after the birth of their daughter in 1920.

In Paris, Schiaparelli’s sense of style emerged. When, in 1927, she wore a jumper with a large white bow knitted into the neckline (featured in the exhibition) to a smart luncheon party, every woman there clamoured for one, including a New York buyer who demanded 40. Within a year, Schiaparelli was running a sizeable business from a small flat, which she painted black and white.

Soon she expanded into sportswear and when, in 1931, the designer added evening gowns to her collections, the business grew exponentially. By 1932 Schiaparelli was employing 400 workers to produce the 70-odd pieces she showed twice a year and in 1935 she moved to a 98-room salon at 21 Place Vendôme.

Then came the years of real fame. Her influence was everywhere, and wherever she went she garnered headlines. Schiaparelli was designing everything from footwear to fashion jewellery for faithful, stylish clients who were her friends as well as her best advertisement.

Schiaparelli was superstitious when it came to naming her fragrances. Just as Chanel believed five was her lucky number, and therefore christened her best-known perfume Chanel No. 5, so Schiaparelli thought everything she created should begin with an S. Thus, her most famous scent, which came in a bottle in the shape of Mae West’s famous curves, was called – what else? – Shocking.

Schiaparelli: Fashion Becomes Art will be at London’s V&A from 28 March. Tickets from vam.ac.uk