My reinvention as a take-no-prisoners consumer rights champion started with my greenhouse.

Thanks to a small fire in my back garden, some cracked panes and singed wood, it needed replacing.

At the time I’d just had a baby and my hands were full with his two older brothers, then two and seven, so I was too busy to scour the Yellow Pages (remember those?) to get quotes.

Instead, I found an advert at the back of the local newspaper: ‘Handyman, can do anything’, alongside a list of skills that included window replacement and carpentry. Perfect.

I rang this person, whom I shall call Richard, and he came to my house in rural Oxfordshire that afternoon to take some measurements.

Richard did lots of nodding and said, yes, he’d use this wood and that glass and it all seemed perfectly in order. It would cost me £2,500 all in, he told me three days later, having costed it up, with £1,250 needed upfront for materials. Cash in hand, if I could, so he could make a start that very week, though at first it would all be off-site.

Look, he seemed an honest man. We knew people in common – not friends, granted, but vague acquaintances. In fact, I very slightly knew his brother. And so I handed over the money and he gave me a receipt and a very short contract saying he’d finish the greenhouse in eight weeks.

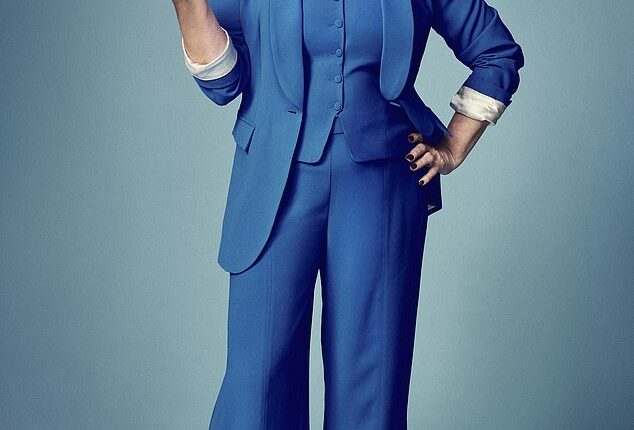

After Richard (not his real name) duped Lucy out of £1,250 for a greenhouse that never appeared, she gave him two weeks to return the money or said she’d file a claim with the small claims court

But you know where this story is going – I waited eight weeks and nothing appeared.

Now, I’m not a pushover. I like to think I am a robust negotiator and a half-decent judge of character. But the infuriating truth is some tradesmen still see women as an easy target. They think we won’t understand technical jargon or we’ll assume they know more than we do and we certainly won’t square up to them, metaphorically speaking, if their work is shoddy or – as in my case – non-existent.

At the time I was living with the father of my children but he was at work all day and it was my house. My greenhouse. My domain and my responsibility. Why shouldn’t I expect to be treated fairly?

I emailed Richard, politely inquiring as to the whereabouts of my greenhouse. No reply, so I emailed again. And again, not once omitting the words ‘please’ and ‘thank you’. I rang – twice a week, three times. I did not shout or demand or threaten.

After a month of this, I managed to get the number of his brother from a friend. There was silence at the end of the phone when I explained what was going on. ‘I hate to tell you this,’ he said, ‘and you haven’t heard it from me, but I don’t think you’re ever going to get that greenhouse.’

His brother was not handy at all, he explained, and had barely ever made anything. ‘But he advertised his services in the paper,’ I said, shocked. The brother gave a hollow laugh. I asked if he could help me get my money back but he didn’t want to get involved.

I was stunned – and angry. Furious in fact. I called the local newspaper but was told there was nothing they could do; it wasn’t their job to vet adverts and this person had paid fair and square for it.

Should I call the police? But I knew contract disputes weren’t strictly a criminal matter. If I’d been a man, I might have tracked him down and paid him a visit but that wasn’t an option either.

Of course, if I’d been a man, I don’t think he’d have tried it on like this in the first place. Richard thought he could dupe me because I was a powerless woman.

Except, all of a sudden, I wasn’t. It’s not very sexy, the small claims court – but boy does it rebalance that power dynamic.

Many people imagine taking someone there is difficult or time-consuming or will cost them more than it’s worth. But none of that is true –and I should know. I have used it five times now and on each occasion not only have I boosted my bank balance but also my self-esteem.

At the age of 59, I have finally learned how to fight back.

Since Richard, Lucy has taken all sorts of people to the small claims court including a plumber, a company that was meant to provide driving lessons, a cashback scheme

A staggering 1.43 million small claims were filed in England and Wales in 2024 (for amounts under £10,000, the threshold beyond which a claim is no longer ‘small’)

I gave Richard two weeks to return my money or told him I’d file a claim with the court. No doubt he thought I was calling his bluff but when two weeks passed and he was still as silent as the grave, I logged on to the online portal and off I went.

This was some time ago and it was less user-friendly than now, though still perfectly doable. I gave the history of the arrangement between us and uploaded documents showing how much money I had paid him and when he said he was going to supply the greenhouse. You can claim interest on money owed but I wasn’t going to make this complicated or punitive – I just wanted my £1,250 back.

You have to pay a fee depending on how much you are claiming for (it’s £35 up to £300 and then goes up on a sliding scale; for my £1,250, you’d nowadays pay an £80 fee).

The person is then informed you have served a claim on them and has 14 days to respond. From this point they can either pay in full, admit part liability, dispute the amount, or ask for more time to pay.

Ten days after I filed my claim, Richard’s brother appeared on my doorstep. He told me his brother was sorry, then handed me an envelope with £1,250 cash in it. I withdrew my case at the small claims court and celebrated my first sweet victory.

Brits are generally a fair bunch and we hate being screwed over. We’re also a nation of form fillers, comfortable with bureaucracy so long as it’s not too burdensome.

In figures that surely give Bleak House a run for its money, a staggering 1.43 million small claims were filed in England and Wales in 2024 (for amounts under £10,000, the threshold beyond which a claim is no longer ‘small’). Only 3 per cent of these went to a hearing, however – the vast majority were ‘undefended’ and resulted in a simple court order in favour of the claimaint or were settled privately and then withdrawn.

Since Richard, I’ve taken all sorts of people to the small claims court.

I filed a claim for £400 against an outfit called PassMeFast, which was supposed to provide driving lessons for my son Jerry but failed to locate an instructor. I spent a lot of time calling, emailing and even messaging the company on X (formerly Twitter) asking why no driving lessons had been booked, but no one ever seemed to answer.

In the end, I found another local teacher and requested my £400 deposit back, only to be told after much further calling that Jerry wasn’t eligible for a refund because his account had been put ‘on hold’.

When emails are marked No Reply and no one ever picks up a phone, you start to lose patience – and mine is no longer as elastic as it used to be.

Blame the menopause or the middle-aged sense that life’s too short, but I refuse to be messed around and left out of pocket any more. Thankfully, the small claims court came to the rescue. Within days of filing a claim, PassMeFast paid me my £400 and the case was settled.

And now we come to a part of this story which I hate re-telling because it makes me feel such a fool.

In 2023, I lost nearly £25,000 to a cryptocurrency scam. Utterly stupidly, I fell for a social media ad featuring the financial expert Martin Lewis – which wasn’t really him, of course – and for an initial investment of £250 found myself caught up in a web of lies and imposters which in the end conned me out of a large part of my savings.

The cast of characters I repeatedly dealt with were hugely plausible but all were fakes – and I was an idiot.

When it came to this vast chunk of money, I had no recourse – the company was bogus and everything untraceable. The money was simply gone and I had handed it over. And all the while I’d thought myself increasingly steely and savvy.

It was devastating and I blame myself – though it shows how easy it is to fall for these people unless you’re constantly on your guard.

But I didn’t let it crush me. Nor my zeal for pursuing smaller-scale stuff through the courts. Indeed, it made me look at my finances with a newly forensic eye, which is how I discovered a company I’d never heard of before – something or someone called completesave.co.uk – had been taking monthly payments from my bank account since September 2020. In all, I’d coughed up £870.

I highly recommend getting in touch with your inner consumer champion. It is enormously satisfying to know the rogue tradesman and the sneering salesman don’t have the upper hand

It took me a while to work out what it was – a cashback scheme which gives you discounts in certain online shops in return for a monthly subscription – but I had no recollection of signing up and certainly didn’t authorise regular payments.

I had no joining email, no membership number, no marketing emails. I contacted the company to close down whatever alleged account I had, only to be told they had no record of me joining their voucher scheme either and could not cancel a membership that no one could prove ever existed.

Obviously, I instructed the bank to refuse all further payments to them – but what of my £870?

Once again, I filed my claim for a repayment and within three days completesave.co.uk arranged to pay the full amount back.

There are limits to this. You can’t claim for emotional reasons. There has to be a legal case.

For example, in the summer of 2024, I hired a plumber I found on local listings to explore a leak in my bathroom. He came out and said he wasn’t sure there was leak, despite clear evidence there was. When it got worse, he came back and grouted and sealed the shower, repaired the damaged plaster and paintwork and charged me £1,500.

Two months later, the leak returned, so back he came but this time said it would cost me a further £1,500 to explore where the leak might be.

Would he have suggested this had I been a man? I don’t think so. He was quoting a ludicrous sum because he either didn’t want to do the work or thought I was a mug. The lack of respect made me furious. I said I wasn’t paying it. He charged me a £100 call-out fee despite not doing anything.

I then asked another highly recommended plumber – who had been too busy originally – to give me a second opinion. His verdict? The original work had been substandard. The leak had been neither diagnosed nor fixed correctly. That made me crosser than ever.

So I took my first plumber to the small claims court for the original payment of £1,500 – the sum I’d spent on his fix that wasn’t a fix.

The main thing you need is a paper trail – photos of the work, invoices, emails, messages, agreements and disagreements. I also had the written report from the second plumber.

The legal position was that the work was below the reasonable standard set out in the Consumer Rights Act 2015. Within a week my money was returned.

The fifth time I resorted to the small claims court (yes, I really do love it) was when I helped my son Raymond make a case against a car hire company which had forced him (me, really) to pay them £2,500 for ‘damaging’ a car he had hired.

They could not show he had signed the paperwork that would make him liable for it – and the two small scratches he admitted to causing should have cost no more than £200 to repair, according to a local garage. Surprisingly, when notified of our claim, the car hire company returned the £2,500, not even deducting the £200 we said they could have.

I have now gained a certain notoriety among my friends and family for resorting to official means to ensure people and businesses are accountable.

I’ve taken Southern Electricity to the Ombudsman for over-charging me.

I took the Department for Work and Pensions to an independent hearing for asserting that I had been fraudulently claiming money during Covid (I hadn’t). I am constantly checking Trustpilot and also putting reviews on it. It takes a lot of time but the satisfaction when I win my cases and people have to pay back money makes up for all the effort and energy I put into it.

My 18-year-old daughter, on the other hand, thinks I am taking it all too far and have become power mad. She found me about to make a claim against a clothing company for a £189 blouse I wanted to return. It was proving impossible due to the return portal not working, the chatbot being ‘unavailable’ and no human ever answering the phone. Emails were bouncing back and I was getting increasingly frustrated. ‘What are you doing?’ she asked.

I told her I was going to file a claim against the company in the small claims court to get my money back.

She sighed. Then she leaned over my computer, fiddled around a bit and pushed a button. ‘There,’ she said, ‘return done.’ It turns out I was clicking the wrong thing.

Even so, I highly recommend getting in touch with your inner consumer champion. It is enormously satisfying to know the rogue tradesman and the sneering salesman don’t have the upper hand. We do. Power to the people.