From the floor-to-ceiling windows of my four-bedroom house just outside St Mawes, on Cornwall’s Roseland Peninsula, I’d watch the yachts sailing across the estuary while I worked from home.

It was a dream seaside bolthole with a sunlight-filled kitchen, polished oak floors and high ceilings accompanying the spectacular views in the heart of an Area of Outstanding Natural Beauty.

Leaving it was probably the hardest thing I’ve ever done.

I still own that place, but nowadays I rent it out to long-term tenants.

It still feels surreal that the idyllic property I worked so hard for is now another family’s address.

When I bought it with my then-fiancé in 2017, I was painfully aware that I couldn’t get life insurance or critical illness cover because of my previous cancer diagnosis.

Nonetheless, we went ahead with the £450,000 purchase, telling ourselves not to let fear dictate our future.

We had two full-time incomes, no children and every reason to believe that it would all work out.

By early 2020, just before lockdown, our engagement had unexpectedly ended and I was in the process of buying my ex’s share of the house. I was suddenly a single parent with a £280,000 mortgage and a lingering sense that I’d pushed my luck too far.

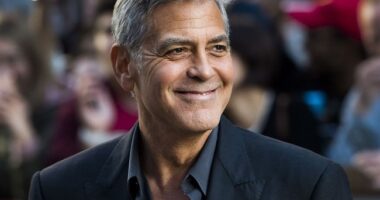

Rebecca Tidy (pictured) managed to pay her mortgage off aged 35 – but she had to give up her dream home in Cornwall in the process

Not to mention the fact that I ran a small buy-to-let business, alongside my day job as a freelance journalist, which looked fine on paper but left me horribly exposed if interest rates ever went up.

I was terrified that I’d become unwell and struggle to pay the mortgage. If anything happened to me, my daughter could be left with nothing. Her father isn’t exactly what you’d term fiscally responsible, so the pressure to create some form of security fell squarely on me.

Overnight, everything I’d worked so hard for – including my beloved home – stopped making me happy and instead felt like a risk.

The uncertainty around my health and financial future was too much to bear. And while I didn’t want to sell it, a hefty mortgage without insurance was undeniably reckless for a lone mother that’d had cancer in her twenties.

So I did the unthinkable and bought a much smaller, scruffier place nearby for £200,000 for my daughter and me, without selling the seafront property, gambling that the profit from renting out the old house to tourists would pay off the new one.

Increasing my borrowing was technically a risk, but I was determined to clear the mortgage on our own home as fast as possible and willing to take any extreme measures necessary. At least my daughter would be financially secure if the worst did happen.

My family thought I’d lost the plot. They all live in big, beautiful houses. You’d have thought I was moving to a third-world country instead of a rundown property in a quiet Cornish village.

When I showed my mum and grandmother around the modest, practical place I’d chosen, they were emotional. I’ve since learned that my mum went home and cried, as she thought we’d never be happy there.

The mother purchased a three-bedroom home (pictured) on a quiet cul-de-sac not far from her original abode

When she first moved in, the house had no central heating or hot water – and the kitchen was ‘hideous’ (pictured is her refurbished kitchen)

It was a three-bedroom semi on a quiet cul-de-sac, not far from my old house, with a garage and tiny garden. But it hadn’t been touched since the eighties. There was no central heating or hot water, and the kitchen and bathroom were hideous.

Worst of all – shock horror – there was only one bathroom. My grandmother is still appalled that I don’t have a downstairs toilet. She’s got no mobility issues, but an inexplicably firm belief that it’s the height of peasantry not to have one.

After cancer, I was unbothered by a bit of material discomfort, but it pained me that my family was upset.

I was confident that I could pay off the mortgage on our new little home in five years by renting out the old place to tourists and throwing every penny of my salary into overpayments, giving me the security I desperately craved.

But though it was undeniably profitable, I couldn’t keep up the constant cleaning, endless DIY and late-night messages from guests between my day job and childcare responsibilities. Even finding and organising reliable contractors felt overwhelming.

I ended up compromising by renting the seafront house to long-term tenants for a much lower rate and less work.

And once I’d ripped up the old carpets, laid new tiles and plastered the walls in our new place, I started renting that one to paying guests instead.

For the last five summers, my daughter and I have packed up and moved into a very unglamorous caravan while tourists take over the house. There was no question of moving in with any of my family. Much as I love them, we’d have driven each other mad.

Rebecca’s family weren’t impressed when they saw the home – and her mother cried after she saw the pictures for the first time

It’s brought in around £12,000 each year, which – combined with my other income – has been enough to make a real dent in the mortgage.

We turned it into an adventure, taking budget-friendly day trips to explore the beaches and spending our evenings outdoors toasting marshmallows.

I’ve worked unthinkably long hours over the last few years, often bringing my daughter Mabel, seven, on my work trips. Every spare penny from my freelance writing and research went straight towards mortgage overpayments.

Over that period, I sold most of my designer things on Vinted including handbags, shoes and clothes from my office days. I made more than £10,000 selling it all, which still surprises me. The fancy car went too, replaced with my mother’s old Peugeot, which freed up another £11,000.

Cancer’s hidden blessing was that it killed off any real interest I had in possessions, so it didn’t feel like a hardship. If anything, it felt freeing.

And in all that time, we took just one budget holiday.

Over the summer, an unexpected need for a replacement floor-to-ceiling window in the seafront house nearly crippled me, and with the cost of everything soaring, the repairs on that place are starting to rack up again now.

I finally paid off the mortgage itself around 18 months ago at the age of 36, and next month I will finish repaying the final instalment I agreed to give my ex after our split.

Family and friends often congratulate me on the achievement. In Britain we treat paying off a mortgage as the ultimate milestone, supposedly proving that you have made sensible choices.

Yet few people acknowledge what it costs. You miss out on fun and freedom.

I’d love to say that being mortgage-free feels better than any sea view. But in truth, I’m unsure it does. It definitely comes with guilt and a quiet sense of longing though.

In Cornwall, space is plentiful and the pace of life is slower. Most of my daughter’s cousins and school friends live in big houses with acres of land, the kind of upbringing I – like many millennials – once took for granted.

I feel a quiet pang of guilt watching her run across their lawns and hearing her stories of ponies and swimming pools.

Our little house looks fine on the surface, though after this last summer the hot water’s broken again, the front windows leak in heavy rain and the cheap DIY kitchen and bathroom are in desperate need of replacement.

I remind myself that my daughter will grow up knowing the value of security instead of just the appearance of it. We may not have everything, but we have our own secure home and that makes every sacrifice across the last seven years worth it.