1944 was an impressive year for the movies, shaped by World War II and a film industry responding with both escapism and hard-edged realism. Hollywood was operating at full power, producing comedies, romances, musicals, and prestige dramas, but beneath that surface ran darker currents of anxiety, moral ambiguity, and psychological tension. The result was the birth of film noir.

Looking back, 1944 feels like a year when cinema proved its resilience, showing that even amid global catastrophe, movies could still interrogate human nature, offer solace, and push the art form forward in lasting ways. Here are the year’s finest classics, ranked.

10

‘Arsenic and Old Lace’ (1944)

“Insanity runs in my family. It practically gallops.” Arsenic and Old Lace is a gleefully macabre comedy that finds humor in the most unexpected places. Cary Grant leads the cast as Mortimer Brewster, a drama critic who discovers that his sweet, elderly aunts have been poisoning lonely old men and burying them in their basement. As Mortimer scrambles to protect them, he must also contend with a criminal brother who believes he is Theodore Roosevelt and another brother who is a full-fledged murderer. All this naturally escalates into full-blown farce, piling misunderstandings and coincidences on top of one another.

Director Frank Capra leans into theatrical energy and rapid-fire dialogue, creating a sense of controlled chaos. The humor is enjoyably wacky, but what’s impressive about the movie is its fearless tonal balance. It treats death and insanity with cartoonish absurdity, never losing its comic rhythm. This style was well-suited to wartime audiences, who craved laughter but were also very much aware of the world’s darkness.

9

‘Murder, My Sweet’ (1944)

“She tried to sit in my lap while I was standing up.” Murder, My Sweet is a cornerstone of film noir, helping to transform the classic hardboiled detective story into something more shadowy and psychologically dense. It focuses on private investigator Philip Marlowe (Dick Powell) as he is hired to find a missing lover, only to stumble into a labyrinth of deception, murder, and obsession. The plot unfolds through flashbacks, voiceover, and shifting allegiances, gradually revealing a world where truth is elusive, and everyone has something to hide.

The atmosphere matches the subject matter perfectly. The movie immerses us with darkness, disorienting camera angles, and surreal dream sequences that mirror Marlowe’s growing confusion. As a result, Murder, My Sweet is less about solving a case than surviving moral corruption. Its cynical tone, sharp dialogue, and psychological unease were hugely influential, and the lean 93-minute runtime means it stays taut and tense throughout.

8

‘To Have and Have Not’ (1944)

“You know how to whistle, don’t you, Steve? You just put your lips together and blow.” To Have and Have Not is a romantic adventure set against the backdrop of World War II intrigue in the Caribbean. The main character is Harry Morgan (Humphrey Bogart), an American fishing boat captain in Martinique who becomes reluctantly involved with the French Resistance after meeting a mysterious young woman named Marie (Lauren Bacall). As political tension rises, Harry must decide whether to remain neutral or risk everything for a cause larger than himself.

The plot is pretty juicy, and the chemistry is off the charts. Bogart and Bacall, two of the brightest stars of the day, electrify the screen. Their flirtation is endlessly fun to watch. Yet beneath the banter and glamour lies a surprisingly smart, perceptive story about choosing sides in a morally compromised world. Directed by the great Howard Hawks, the film balances lightness and seriousness with remarkable ease.

7

‘Meet Me in St. Louis’ (1944)

“All right, then. I hate you.” Meet Me in St. Louis is a warm, nostalgic musical that captures the rhythms of family life at the turn of the twentieth century. Set over the course of a year, it follows the Smith family as they experience love and disappointment. The plot is episodic rather than dramatic, focusing on small moments instead of grand conflict. Director Vincente Minnelli uses color, music, and domestic detail to evoke a sense of comfort and continuity. This emotional sincerity may not be for everyone, but the right kind of viewer is sure to appreciate it.

The themes have a universal appeal. In particular, the movie celebrates ordinary joy while acknowledging the pain of change and loss. This message very much resonated with audiences on release; Meet Me in St. Louis went on to become the second-highest-grossing film of the year. Not for nothing, its songs and imagery have become deeply ingrained in American culture.

6

‘Gaslight’ (1944)

“I am not imagining things.” In recent years, the term “gaslighting” has entered common parlance, and it owes its origins to this psychological thriller. Gaslight centers on Paula (Ingrid Bergman), a young woman who moves into her late aunt’s London home with her husband (Charles Boyer), only to be subtly convinced that she is losing her sanity. Strange noises, dimming lights, and missing objects all seem to confirm her fears. As the plot unfolds, it becomes clear that these events are part of a calculated effort to control her.

Although generally known for lighter, cheerier fare, director George Cukor handles the tension and atmosphere incredibly well, building suspense through suggestion rather than overt violence. In the process, the story exposes how trust can be weaponized and how easily reality can be distorted by those in power. The fact that we still reference it today, whether consciously or not, speaks to its cultural impact.

5

‘Lifeboat’ (1944)

“We’re in the same boat.” Although not necessarily one of Alfred Hitchcock‘s most famous movies now, Lifeboat remains an absolute banger. It’s a bold wartime thriller set almost entirely on a single boat adrift in the ocean, a conceit only a director of Hitch’s skill could’ve pulled off. After a ship is sunk by a German submarine, a group of survivors from different backgrounds are forced to coexist in a lifeboat. Among them is a captured German officer (Walter Slezak) whose intelligence and discipline prove uncomfortably useful.

Here, the Master of Suspense turned limited space into a pressure cooker, where ideology and prejudice clash under extreme conditions. The plot is a little pulpy and very entertaining, but the themes deliver, too. As the characters debate whether humanity or pragmatism should guide their decisions, Lifeboat uses its premise to explore survival, suspicion, and moral compromise. In short, the film refuses easy answers, suggesting that moral certainty becomes dangerous when survival is at stake.

4

‘Going My Way’ (1944)

“There’s nothing like a good song to lift the spirit.” This was the biggest commercial hit of the year, grossing over $6.5m (a whopping sum for the time). It also took home the Best Picture Oscar, perhaps because its heartfelt message about faith, community, and generational change spoke to a war-weary public. In it, Bing Crosby plays a young, unconventional priest assigned to help an older clergyman (Barry Fitzgerald) struggling to keep his parish afloat. Through music, kindness, and quiet persistence, the newcomer revitalizes the church and reconnects it with its congregation.

The plot unfolds through small conflicts and reconciliations rather than dramatic crises. Refreshingly, the movie manages to be warm without being cheesy or try-hard. Director Leo McCarey (known for directing the Marx brothers classic Duck Soup) avoids sentimentality, grounding the story in human relationships instead of doctrine or ideology. The result is a sweet statement on the power of empathy and humility.

3

‘Ivan the Terrible, Part I’ (1944)

“Power reveals the soul.” Ivan the Terrible, Part I is a monumental historical epic with a strong side of political allegory. It chronicles the rise of Ivan IV as he consolidates power in sixteenth-century Russia, battling internal betrayal and external threats. We watch as he transforms from idealistic ruler to increasingly paranoid autocrat. The subject is fascinating, though it’s the movie’s style that really makes it stand out. Here, Sergei Eisenstein uses exaggerated performances, stark lighting, and symbolic composition to turn history into myth. Every gesture and shadow feels loaded with meaning.

Created under Stalin’s regime, the film doubles as a meditation on absolute power and its psychological cost. The parallels with the leadership of the Soviet Union are plain to see. While Part I was officially praised, its darker implications were unmistakable. Over time, the film has been recognized as one of the most visually ambitious historical dramas ever made. In hindsight, many now regard it as one of Eisenstein’s most complex works.

2

‘Laura’ (1944)

“I fell in love with Laura.” Laura is an elegant noir mystery steeped in obsession. Here, detective Mark McPherson (Dana Andrews) investigates the apparent murder of Laura Hunt (Gene Tierney), a successful advertising executive admired by many. As he interviews suspects, Mark becomes increasingly fascinated with Laura herself, despite believing her to be dead. The plot twists and turns delectably, challenging assumptions about identity and desire. Not to mention, there’s an abundance of exquisite mood.

Indeed, the movie conjures up a dreamlike atmosphere where love and suspicion blur together. Laura becomes less a person than an idea, shaped by the projections of others. Through her, the film explores how obsession can distort truth and morality. It reminds us that idealization can be as dangerous as hatred. This sophisticated blend of romance and noir would inspire countless copycats. Finally, on the aesthetic side, the lush score and refined visual style elevate the mystery into something almost hypnotic.

1

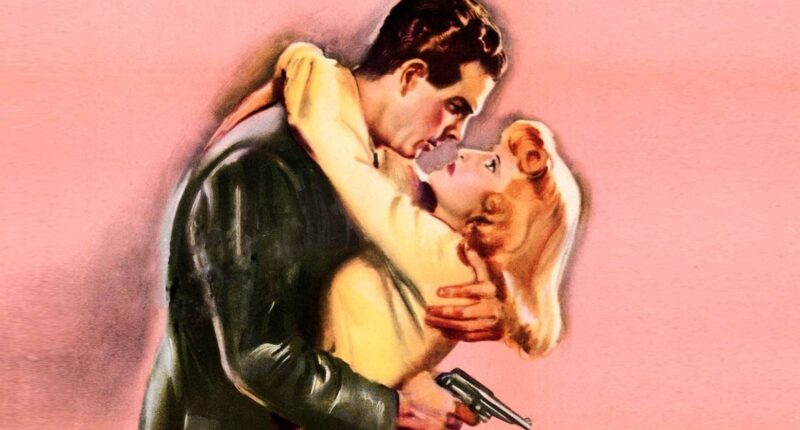

‘Double Indemnity’ (1944)

“I love you, too.” Double Indemnity is one of the definitive film noirs, a razor-sharp tale of lust, greed, and inevitable ruin. Fred MacMurray delivers a terrific lead performance as insurance salesman Walter Neff, who conspires with a seductive woman (Barbara Stanwyck) to murder her husband and collect on a policy with a double payout clause. The plot unfolds through confessions, tracing how small moral compromises spiral into catastrophe. The characters are driven not by desperation alone, but by arrogance and desire.

The moral darkness here is real, with a focus on the rot that exists beneath respectable surfaces. Some audiences even found this a little shocking for the time. That said, it never gets exploitative or overly melodramatic. Billy Wilder, one of the finest filmmakers of the era, handles the material with assurance and precision. The narrative structure is airtight, ensuring that every decision carries weight. For this reason, Double Indemnity more than holds up all these decades later.

d