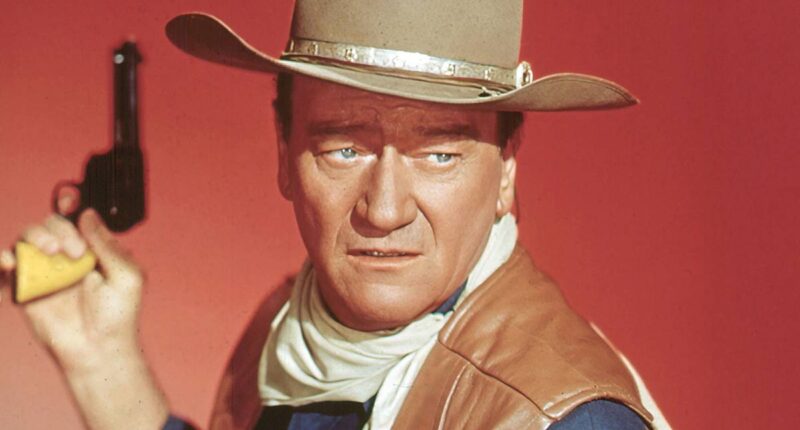

Of all the things that John Wayne was during his career, chill was never one of them. One of the most iconic movie stars and symbols of American pop culture in history, Wayne never shied away from calling out trends in movies that upended his social and political beliefs or picking beefs with actors, particularly up-and-coming young stars looking to steal his thunder. As he aged, he only became more of a curmudgeon, if not a downright racist. Wayne’s feud with Clint Eastwood, his successor as the signature face of the West on screen, is well documented, as he vehemently condemned the actor-director’s dark interpretation of American myths. During the later years of his life, Wayne inexplicably took umbrage against one of Eastwood’s future co-stars, the late Gene Hackman, whom he once referred to as “the worst actor in town.”

John Wayne Called Gene Hackman “The Worst Actor in Town”

By the time Gene Hackman emerged onto the scene in the late ’60s and early ’70s, John Wayne was winding down, appearing in his final film in 1976, The Shootist. This era of Hollywood, colloquially known as the New Hollywood, was a changing of the guard, with movie-obsessed directors from film school being given studio resources to make subversive, challenging, and groundbreaking films that reconsidered the nobility of America’s history and contemporary life amid the decade’s social and political upheaval. The era’s movie stars, including Al Pacino, Robert De Niro, Jack Nicholson, and Hackman, had a darker, haunted edge, unafraid to paint themselves in an ugly light.

In meme language, John Wayne was Grandpa Simpson yelling, “Old man yells at crowd.” His last decade alive was synonymous with notorious moments, such as writing a letter of disgust to Clint Eastwood after watching High Plains Drifter and the legend of his near-violent response to Sacheen Littlefeather‘s speech at the Oscars in 1973. During this period, Gene Hackman, the Oscar-winning star of The French Connection, caught strays from the Duke, according to his daughter, Aissa Wayne, in her book, John Wayne: My Father.

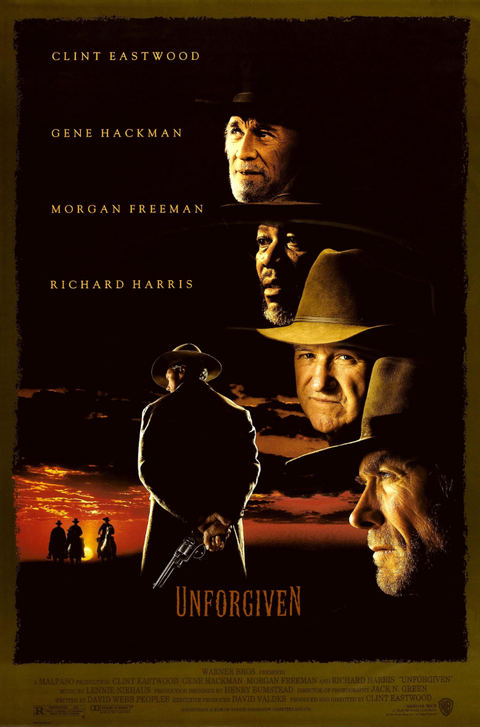

“Gene Hackman could never appear on-screen without my father skewering his performance,” Wayne’s daughter wrote, claiming the future Oscar winner for Unforgiven was her father’s lone source of venom. Wayne never elaborated on what rubbed him the wrong way about Hackman, but he was quick to disparage his name, calling him “the worst actor in town” and “awful.” According to Aissa, had her father lived to see more of his work, “his view of Mr. Hackman would have changed.”

Generational animosity wasn’t always his source of vitriol, as Aissa also recalled that Wayne was frequently critical of Clark Gable, calling him “dumb.” She speculated that, because Gable clashed with Wayne’s favorite director, John Ford, on the set of Mogambo, this was merely a case of him sticking up for his creative partner.

Gene Hackman Represented a Shift in Movies Away From John Wayne’s Worldview

By today’s standards, Hackman, known for his grizzled and menacing characters, represented a traditional form of hard-edged masculinity that should’ve been right up Wayne’s alley. Hackman didn’t need to age into his ’60s and ’70s to become more seasoned, as, like many of his contemporaries, he always registered as an older man with gritty sensibilities. While far less problematic, Hackman was also known for his occasional prickly and combative streak, evident in his clashes with Wes Anderson when making The Royal Tenenbaums. Like Wayne, Hackman possessed a distinct screen persona and hardly transformed into any roles, but his sturdy presence as a brute force was built for the big screen.

Hackman played authority figures like Jimmy “Popeye” Doyle in The French Connection, Reverend Scott in The Poseidon Adventure, and Major Gen. Sosabowski in A Bridge Too Far, each of which could’ve been played by Wayne in the 1950s. However, Hackman brought a subversive quality to these morally ambiguous characters who challenged Wayne’s idyllic and staunchly naturalistic portrait of American exceptionalism. With The Conversation and Night Moves, two quintessentially bleak New Hollywood films about institutional distrust and angst, his characters are only heroic within the confines of his near-dystopian worlds.

Perhaps John Wayne would’ve taken more of a liking to Gene Hackman’s later body of work, like Crimson Tide and The Quick and the Dead, roles built on sheer gravitas. If he ever lived to see Unforgiven, his Western disciple Clint Eastwood’s permanent deconstruction of the genre and the nobility of the outlaw, Wayne would have tried to make a citizen’s arrest on Eastwood. The times were rapidly changing, and a radical new movement in Hollywood began reflecting these times, so Wayne was destined to be a grump about everything.

- Release Date

-

August 7, 1992

- Runtime

-

130 Mins

- Writers

-

David Webb Peoples