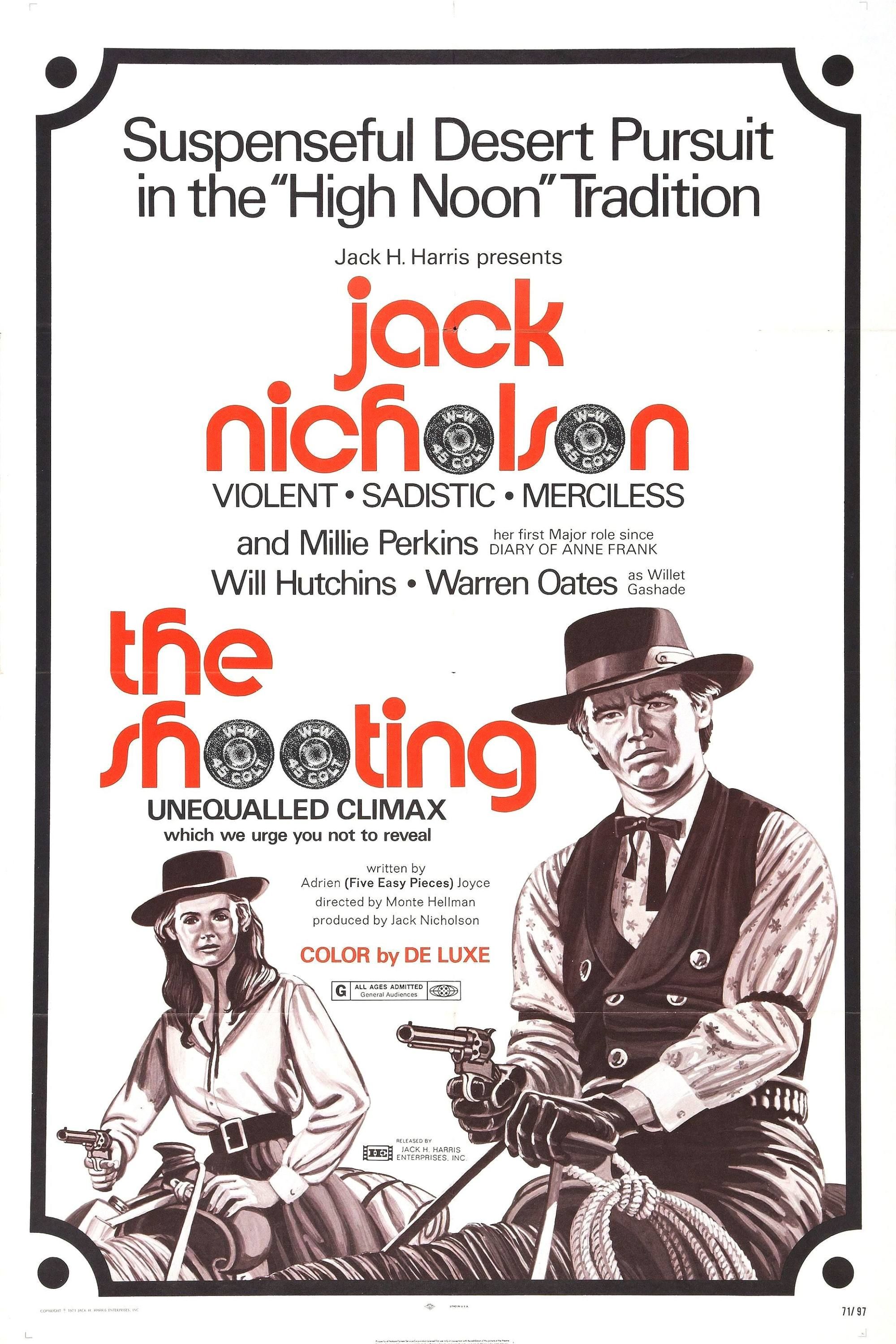

Long before revisionist Westerns became a thing, Roger Corman, as an uncredited executive producer, teamed up with director Monte Hellman to make the 1966 psychological Western The Shooting. It is one of the earliest movies to rewrite the rules of its genre. The film’s low-budget, minimalist approach makes it even more astounding. While it might not have had a roaring reception back then, with distributors showing no interest in providing a theatrical release, The Shooting received positive reviews from critics. And its 100% Rotten Tomatoes score indicates that Hellman’s little cult classic still hasn’t lost its bite.

‘The Shooting’ Is One of the Earliest Westerns to Break All the Rules

The film is a haunting, surreal journey across an unforgiving wasteland. It features four main characters: a mysterious woman with no name (Millie Perkins) and a trio of men she hires to get her across a desert. The woman is possibly on a revenge mission, though her motive is only hinted at. The story is told from the perspective of one of the hirelings, Willet Gashade (Warren Oates), a former bounty collector who agrees to help on the condition that his paranoid and slow-witted friend, Coley (Will Hutchins), accompany them. The woman doesn’t disclose their destination or the reason for the journey. Deep in the desert, the two men find out that they are being trailed by a mysterious gunslinger, Billy Spear (Jack Nicholson), whose presence is akin to the desert’s agent of death. What begins as a Western existential “road movie” morphs into a survivalist narrative.

The desert’s scorching, sun-blasted wasteland is a character in and of itself. There’s no life in sight: no water, no shade. Its empty vastness, captured in Hellman’s wide shots, makes the characters appear absolutely insignificant. Nothing within the landscape cares about their conflicts. It’s as if Hellman is mocking the idea that a lone Western hero can bend the world to his will; his protagonists have no heroics. Gashade is presented as brave and loyal, with a somewhat moral conviction to do good, but when this is put to the test in the desert, he falters. Nicholson’s Billy Spear is a terrifying gunslinger who is also worn down by the harshness of the desert. Coley is consumed by his folly, while the woman often breaks down, overwhelmed by the journey. And while the title suggests a full-blown gunfight climax, there are only two shootings in the genre’s sense of the word throughout the film. And they offer little to dwell on—but that’s exactly Hellman’s point. He infuses Western tropes and then subverts them, so that even the film’s ambiguous ending reinforces Hellman’s critique of grandeur and heroism in the Western.

Jack Nicholson’s Quiet Menace and Monte Hellman’s Vision Make ‘The Shooting’ Unforgettable

What’s even more mesmerizing about Hellman’s minimalist approach is that tension doesn’t suffer at all. He uses the ambiguities of his narrative to pull his audience in. For instance, just like his protagonist Gashade—whose morbid curiosity makes him trudge on to the very end of the journey—you become increasingly interested in finding out where the story is headed. Like Gashade, the more you sense that something sinister is coming, the more you’re drawn to finding out about it.

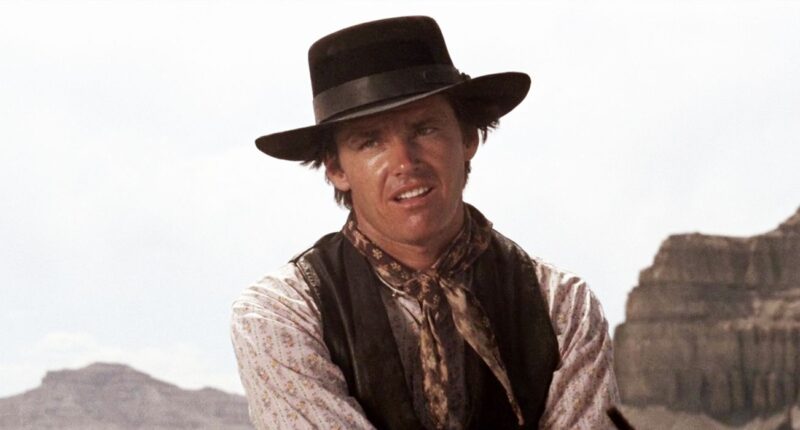

Nicholson, who is also a co-producer of the film, is all simmering menace. His performance leans into stillness. Clad in black and barely uttering a word, he is a haunting frame. Everything he does is calculated to terrify. He quickly draws his gun on his companions for no reason. He speaks slowly. And he dishes out death threats with a chilling grin. Perkins, by contrast, plays the unnamed woman with an unreadable detachment. And she stays that way even in her emotional expression; her silence is a weapon that keeps her several steps ahead of the men around her while rarely giving the audience an emotional handhold. Nicholson and Perkins transferred their dynamic in The Shooting to Hellman’s adjacent movie Ride in the Whirlwind, which was shot immediately afterward.

Related

59 Years Ago, Jack Nicholson Starred in Two of the Best Westerns of All-Time — And Wrote One of Them

Double the Jack Nicholson, double the fun.

Warren Oates as Willet Gashade is the reluctant guide trying to make sense of the woman’s motive while struggling with his own guilt. His way of atoning only drags his friend Coley into more chaos. Oates thinks before he acts, but it’s clear something is eating at him. His restraint makes Gashade real in a survival situation. Will Hutchins as Coley may not get the accolades he deserves, but he is the odd heartbeat that the film needs. Through his babbling, often nervous laughter, and even simping, he is as irritating as he is heartbreaking. You’ll enjoy his comic relief but also empathize with the tragic naiveté he embodies.

Hellman paints his characters’ ruthless world with silence and sand. His gunfights are quick, cold, and empty. His mission is to dismantle the Western myth of grandeur and gun-slinging glory. He succeeds in letting The Shooting provoke the question, “What is all that riding and dying in Westerns really for?” If you’re looking for catharsis, The Shooting will not offer it. Instead, it is a slow drip of dread and a growing sense that this road trip may be a one-way ticket to nowhere. And that’s why it is an essential film for Western enthusiasts.

The Shooting

- Release Date

-

October 23, 1966

- Runtime

-

82 Minutes

- Director

-

Monte Hellman

-

Warren Oates

Willett Gashade

-

Will Hutchins

Coley Boyard