The African-American community will eternally be grateful to legendary composer and producer Quincy Jones. Michael Jackson’s “Thriller” continues to haunt me, the wild and funky Sanford and Son theme, the fantastically youthful Fresh Prince of Bel-Air, our very own The Wiz (1978) which has widely become a community litmus test as strong as one’s ability to jump in on a line dance, and who can forget the incredibly emotional 1985 film adaptation of Alice Walker’s The Color Purple. The list goes on. Jones left his fingerprints on just about any household theme and title buzzing through Black homes across the decades. His rhythm-infused music, like his groovy “Soul Bossa Nova” which was used in the Austin Powers movies, has never lost its power to command our bodies to move; to instill an irresistible urge to tap into our littlest toe bones.

I May Be Young, But I Can Still Appreciate the Legacy of Quincy Jones

Speaking as someone younger than 30 years old in the year 2024, I can’t claim to know every title and melody that Quincy Jones laid his hands on. But I can attest to the timelessness of his work. In the early stages of identifying myself and understanding my family’s culture as African-American, Quincy Jones had been involved in much of what I was able to grasp about Black culture. For example, I remember hearing the sound of Jones’ theme for Sanford and Son on a recurring radio segment, during which there was always laughter and jovial conversation between the radio hosts. But I didn’t know the context of the theme. The show was way before my time, and it’s nowhere to be found in my memories of watching the giant TV that sat in my grandmother’s family room where I spent most of my youth. Yet the show’s theme alone became a familiar, foundational sound of my childhood, and it remains a core fragment in the soundscape of my memories.

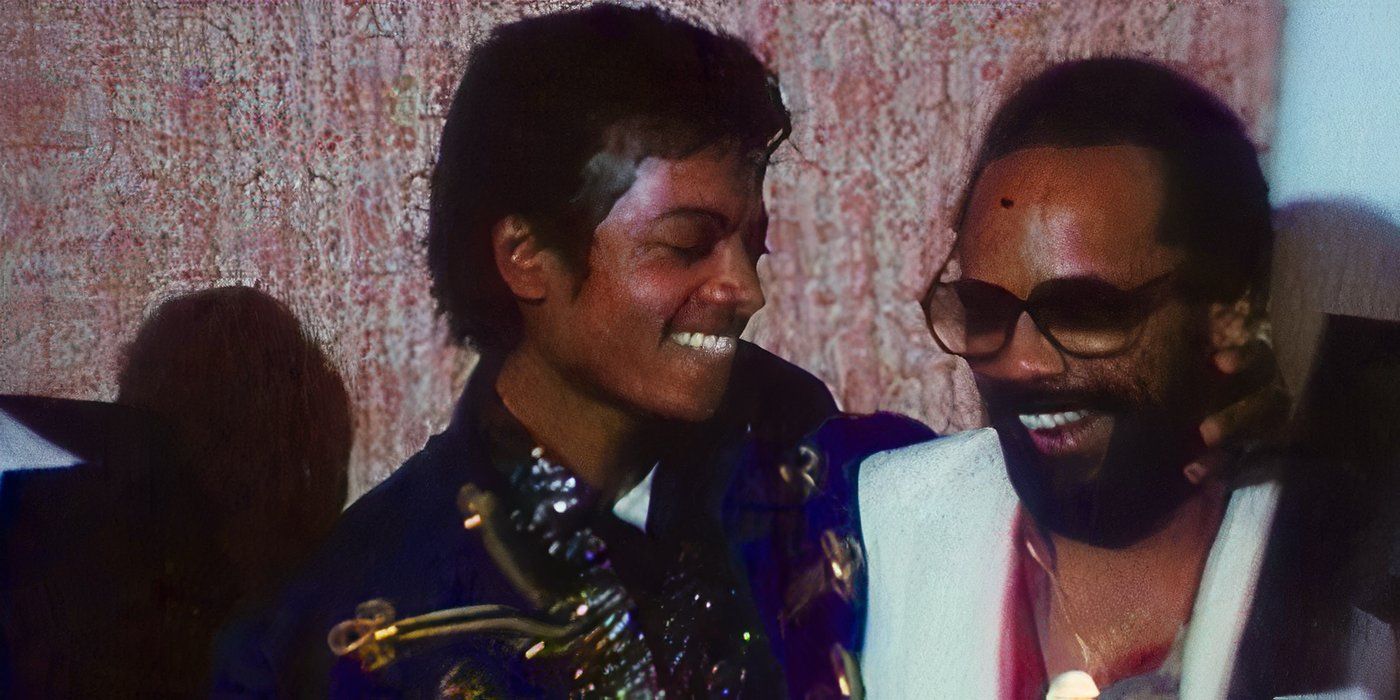

As a child who became a fan of Michael Jackson because he died (an exclusive club), I was legitimately scared when I first watched his wildly esteemed “Thriller” music video. It haunts my dreams on occasion even now (I hold my breath through every single Halloween), not only for its spooky practical and special effects, but in large part for its familiar groove, potent harmonic choices, and classic horror sound effects. Though they culminated in a childhood trauma, these are elements which I can appreciate as a slightly older and educated musician. The entire production was a successfully terrifying marvel, and it’s no surprise Quincy Jones had anything to do with it, especially given his effectual relationship with Michael Jackson.

Related

Antoine Fuqua’s Michael Jackson Biopic Just Moonwalked Its Release Date Back Several Months

Might the King of Pop have some luck on the awards circuit?

Quincy Jones Defined Black Entertainment for Generations

Growing up, I learned very quickly which cultural staples proved one’s “Blackness”. At some point or another, most of my Black peers and I gave each other the litmus tests of “You’ve seen The Wiz, right?” – whose music was largely arranged by Jones – and “Do you know The Color Purple?” – which gave Jones his debut credit as a film producer. To manage one famous lyric or iconic scene would suffice but, although the film adaptations predated us by roughly twenty years, an evident lack of exposure could leave a paper-cut-sized wound in your reputation as a true African-American. Factors like households having different tastes in entertainment, or simply the adults in our families not owning copies of the films, didn’t occur to us. We just recognized that those were things we were supposed to have in common with each other.

The Wiz, a Black reimagining of The Wizard of Oz, was a movie musical I’d grown up on, and it was something that defined my affinity for musicals before I’d even reached the fifth grade. As a kid, what I knew was that the movie was entertaining to watch, that the actors reminded me of my own family members, that it creeped me out, and, ultimately, that it was an emotional story considering I had to shut it off before Lena Horne and Diana Ross tearfully brought the whole thing home. Nevertheless, Quincy Jones’ music for The Wiz sticks with me today as a cornerstone of my music taste, as it incorporated gospel, funk, jazz, and even classical elements that became a colorful exploration of the Black sound (which I now find highly reminiscent of composer William Grant Still’s 1930 “Afro-American Symphony”).

The Color Purple was a movie I learned to be vastly quotable thanks to my mother dropping lines on a regular basis but rarely ever putting on the movie, which often caused me to feel left out of my own culture as a kid. Likely because I was too young to understand its themes of patriarchy, misogyny, sexuality, and the post-Reconstruction era, I was simply too unexposed to The Color Purple to take part in holding my head high as a Black kid – as a Black girl – who knew nothing more than the characters’ names and that thing Celie did with her hand in that one scene. Quincy Jones served as both producer and primary composer for The Color Purple, making history as the first composer to work under Steven Spielberg who wasn’t John Williams. Of course, I didn’t pay much attention to Quincy Jones’ name, let alone recognize his role at the heart of these productions until much later.

Quincy Jones Gave Producers a Wonderful Name

When I began to study music and film, I came to appreciate the title of “producer” (despite its vague, catch-all meaning) by way of Quincy Jones’ work. He was the star behind the star, working with the cream of the crop and granting music careers like a fairy godmother. The Netflix documentary The Greatest Night in Pop had officially enlightened me about the all-around guts he possessed as a shepherd of stars and an entertainment visionary.

As the story goes, Hollywood royal and civil rights activist Harry Belafontesaw a need for Black folk to help other Black folk, so he called on the newly solo-flying Lionel Richie, who instinctively called on Stevie Wonder, Michael Jackson, and Quincy Jones. While it was without a doubt a group effort, the 1985 “We Are The World” recording session was one of the strongest examples of Quincy Jones’ determination, ambition, and problem-solving agility. He had one shot to pull off the recording session of a lifetime, which meant only the right decisions needed to be made, and at lightning speed. Recording engineer Humberto Gatica recalled in the Netflix documentary, “Quincy Jones was always very calm. His only concern was time,” and singer Huey Lewis reflected, “Quincy was amazing. Production is an interesting thing. You gotta be more than a great musician. You gotta be like a psychiatrist.”

The “We Are The World” recording session demonstrated that Quincy Jones knew talent and that he knew humans. In mapping out the artists’ solos, Lionel Richie had envisioned individual booth recording sessions. However, a savvy Quincy Jones saw such a process taking forever and opted instead to have the artists stand in a circle, facing each other as they performed their solos. He kept everyone vulnerable to bring out the best results. Before the artists arrived at the session, he had written out and taped up a sign that read, “CHECK YOUR EGO AT THE DOOR.” When the performers finally started showing up, without agents or managers present and free from the public eye, they mingled as individuals, surprisingly starstruck by one another. Added to the factor that they were coming off of the American Music Awards just hours before, energy was high before rehearsal could begin. But Quincy tagged Bob Geldof, co-founder of charity supergroup Band Aid, to draw attention to the focus of the project with a speech that reflected on his experiences in Ethiopia.

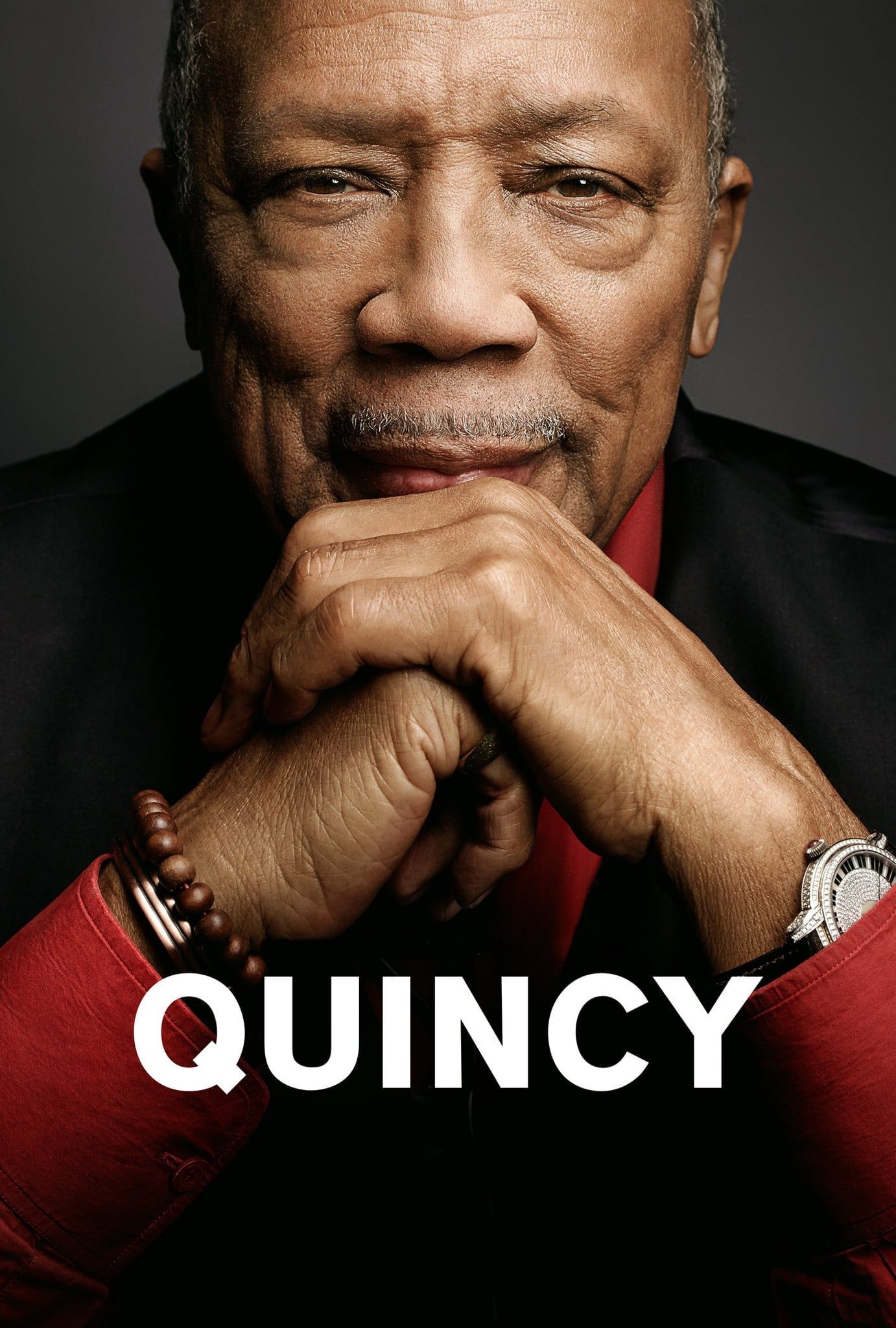

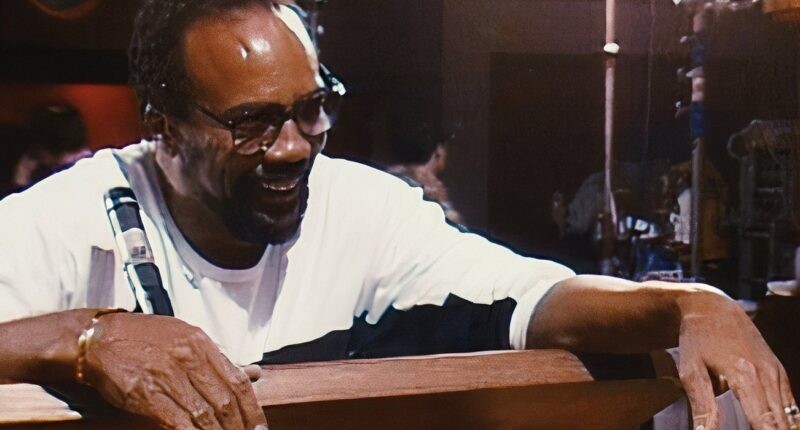

Quincy Jones Was Entertainment History

Quincy Jones built a diverse repertoire of music and film that has inspired generations of entertainers and music-makers. Co-directed by his daughter Rashida Jones and documentarian Alan Hicks, Netflix’s Quincy (2018) examines his background as an instrumentalist that blossomed into his volumes of life experiences as a composer, arranger, and general culture creator amid America’s murky cultural shifts and eras. We’ll be carrying his creations in our laughs and scats, at our cookouts and reunions, and in the little bit of dancing we do down the sidewalk when we’re feeling ourselves. He wasn’t just a massive influence on entertainment. Quincy Jones was entertainment. I may not be the most experienced musician and film lover around, but I can truthfully appreciate what an honor it was to share the world with him for a little while.

Quincy is available to stream exclusively on Netflix in the U.S.

Quincy

WATCH ON NETFLIX

![Michaela McManus Is on the Hunt For a Twisted Killer In a New ‘Redux Redux’ Image [Exclusive]](https://citigist.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/11/Michaela-McManus-Is-on-the-Hunt-For-a-Twisted-Killer-260x140.jpg)