The ’70s were a massively consequential and influential decade for cinema. Between the rise of New Hollywood and the birth of the modern blockbuster, it was an era of filmmaking that brought with it new voices and incredible films whose influence continues to echo through cinema today. There are simply too many great ’70s movies to satisfactorily sum up the decade with only ten movies, even when limited to one per genre. Every category is well represented within the decade, with some of the best films in those respective genres often considered the best of all time, irrespective of their time period.

Action, Animation, Comedy, Drama, Epic, Fantasy, Horror, Science Fiction, Thriller and Western. All are well represented by the cinema of the ’70s in some of the most iconic films of all time, made by some of the greatest filmmakers ever. Even though there are literally dozens of films from the decade that could have slotted into each of these categories without a great deal of argument, and subjectively, everyone who is a film fan could have their own vastly different selection that would be valid, there’s no doubt that these ten ’70s movies still represent the best of their genres.

Action – ‘The Spy Who Loved Me’ (1977)

While the ’70s were still a very nascent decade for the burgeoning action genre, which would burst into full formation in the ’80s, there were still so many incredibly influential action films released, from the gritty thrills of the original Mad Max or Assault on Precinct 13 to the popular martial arts classics best exemplified by Enter the Dragon. If there’s one action hero that has to be paid tribute to, however, it’s James Bond, who started the decade with the final EON film appearance of Sean Connery before ceding the role to Roger Moore, whose far and away best outing as the spy was in 1977’s The Spy Who Loved Me. A globe-trotting adventure with spectacular stunt work, memorable villains and the right balance of tongue-in-cheek humor, it’s a big-budget extravaganza befitting the iconic character.

Titled after the Ian Fleming novel but taking none of its plot other than a certain steel-toothed henchman, the movie follows Bond as he teams up with KGB agent Anya Amasova to take on the original antagonist Karl Stromberg, who has designs on wiping out humanity and restarting civilization underwater. It’s an incredibly silly and campy plotline, as was typical under Moore’s tenure with the character. However, he had become so comfortable with the character by his third go-round, and the action and humor are all staged with such a breezy conviction that it fully wins the audience over. Moore had been the Bond actor for an entire generation, but even those who didn’t groove on his particularly cheeky take on the character had to admit that The Spy Who Loved Me rocks.

Animated – ‘Fantastic Planet’ (1973)

Calling animation a genre is a controversial stance to take, since it truly is a medium whereby all manner of different genre stories can be told; still, for the purposes of this list, it will be treated as such. The ’70s were a bit of a fallow period for Disney, with many of their animated films struggling to make an impression on audiences and at the box office, though many now have become far more beloved, with the best being The Many Adventures of Winnie the Pooh. The era also saw the rise of a number of more adult-oriented animated films and filmmakers like Watership Down and director Ralph Bakshi, who gave audiences subversive films like Wizards and Fritz the Cat. Alas, if there’s one film that edges them all out, it’s the gorgeously surrealistic Fantastic Planet.

Directed by French director and animator René Laloux and based on a novel by Stefan Wul, Fantastic Planet is set on an alien planet where giant blue beings are the dominant species and humans are treated as animals, kept as pets and running wild. Allegorical readings of the film have obviously prescribed a number of different readings to its premise, be it animal cruelty, civil rights, or any number of specific historical events. It’s a film that can be enjoyed through deeper interpretations or just as an experiential experiment thanks to its psychedelic visuals and soundtrack. Fantastic Planet is the exact kind of animated film one would expect to come out of the ’70s, in the best way possible.

Comedy – ‘Young Frankenstein’ (1974)

Satire and slapstick were the name of the game for comedy films in the ’70s, best exemplified by classics like Monty Python and the Holy Grail, M*A*S*H, or The Jerk. If it’s pure and pessimistic satire, then there simply isn’t any better than Sidney Lumet and Paddy Chayefsky‘s Network, which remains just as potent and prophetic today. However, for belly laughs, no filmmaker of the decade had a better track record than Mel Brooks, who spoofed Alfred Hitchcock with High Anxiety and homaged the early days of cinema with Silent Movie. He had his best year ever in 1974 with two certified comedic masterpieces: the Western satire Blazing Saddles and the near-perfect Young Frankenstein.

The latter was co-written by Brooks and star Gene Wilder as both a love letter and a pie-in-the-face to classic horror films and was accordingly made with incredible attention to detail. Shot in black and white with vintage scene transitions and even incorporating some of the lab equipment from the original Frankenstein into its production design, the film is a perfect visual companion to the Universal classics but played with Brooks’ trademark anarchic spirit. By taking the original elements of the Frankenstein franchise and dialing them up to just the right level of ludicrousness, as best represented by the hilarious scene between Peter Boyle‘s monster and Gene Hackman‘s kindly blind hermit, Young Frankenstein walks the tight rope between humor and classic horror with acrobatic ease.

Drama – ‘The Godfather’ (1972)

All That Jazz, Chinatown, Jeanne Dielman, Kramer vs. Kramer, One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest, Rocky. There’s no limit to the masterpieces of the ’70s that fit within the always nebulous drama genre, but there honestly are only two films that could rightly be listed here, and they are both part of the same saga. Francis Ford Coppola‘s The Godfather and The Godfather Part II represent one of the greatest achievements in American cinema, elevating Mario Puzo‘s gangster novel into two sprawling crime drama masterpieces that truly feel as if they should be considered as one full meal. For simplification purposes, the spot goes to the original classic. Chronicling the Corleone crime family as they vie for power in New York City, the film was a watershed moment for gangster movies, with a depth of characters and culture that was heretofore unseen within the genre.

The Godfather depicted organized crime with such complexity that it influenced how real-life gangsters portrayed themselves. The cast is true perfection, from the iconic and constantly imitated Marlon Brando as the titular patriarch, to James Caan‘s hair-trigger-tempered Sonny, John Cazale‘s ineffectual Fredo, Robert Duvall‘s consigliere Tom, Dian Keaton‘s sadly tragic Kay and, above all, Al Pacino as the corrupted soul of the film, Michael Corleone. His fall from morality and rise to power as the new head of the crime family is as operatically tragic as any tale from antiquity and gives the plot its dark beating heart. The Godfather was hailed as a masterpiece on its original release and has held its seat at the head of the table ever since.

Epic – ‘Aguirre, the Wrath of God’ (1972)

The Godfather could just as easily slot in as the greatest epic of the ’70s, as could Coppola’s Apocalypse Now, Stanley Kubrick‘s Barry Lyndon, or Franklin J. Schaffner‘s Patton. Alas, if there’s one film that truly embodies the essence of epic filmmaking, it’s Werner Herzog‘s Aguirre, the Wrath of God. It follows the infamous Klaus Kinski as the titular conquistador who leads a group of explorers through the treacherous Amazon in search of the legendary El Dorado. The film’s epic storyline was matched by its notorious production, which was shot entirely on location in South America, with the actors battling the elements.

While apocryphal stories have been printed about Herzog directing Kinski at gunpoint, it is at least true that the two men were antagonistic to each other, bringing out a volatile passion that comes through in the film. The exhaustion, fury and pure devotion on the faces of the actors come through in every frame, and the film itself takes on a fever-dream-like quality that leaves viewers feeling bruised and battered by the end. Epics like Aguirre, the Wrath of God, simply aren’t made anymore, and for good reason, but it has endured as a piece of film mythology.

Fantasy – ‘Star Wars’ (1977)

The fantasy genre has a relatively thin representation in the ’70s compared to other genres, but nonetheless has some sterling examples, perhaps none more iconic than George Lucas‘ space-fantasy blockbuster Star Wars. Remixing everything from Flash Gordon serials to Akira Kurosawa‘s The Hidden Fortress into a bold hero’s journey with landmark visual effects, Lucas’ passion project was a major risk that paid huge dividends for the filmmaker, especially thanks to the lucrative merchandising rights he retained from the shortsighted executives at 20th Century Studios, then 20th Century Fox.

There’s almost little else to say about Star Wars and its massive impact on pop culture that hasn’t been said a hundred times before in the many years, movies, and series that have passed since the original film’s release. Except that there truly will never be a blockbuster quite like it, as the unique circumstances in which it was released could never be replicated in today’s media-consuming landscape. Star Wars tells a fantasy story as old as time, and it never gets old.

Horror – ‘The Exorcist’ (1973)

Filmmaker William Friedkin had as good a run in the ’70s as any other filmmaker, and he made films that could take the top spot as the best of their respective genres, but where he does take it is with the unparalleled horror of The Exorcist. With the same scale of Jaws, the relentless terror of The Texas Chainsaw Massacre, and the visual acuity of Halloween, Friedkin’s satanic masterpiece adapted William Peter Blatty‘s novel, with a screenplay by the writer himself, and brought the devil into American households. Despite a number of sequels, including the highly underrated third film directed by Blatty, and numerous rip-offs, no film has ever been able to match the raw power of the original.

Following the possession of a young girl in Georgetown, the film set the foundations for all future exorcism films to follow, with a mix of pure performance and twisted body horror effects that is still unsettling. The performances of Linda Blair as the young Regan and Ellen Burstyn as her terrified mother are what bring the true horror of the film alive, along with iconic work from Max von Sydow in the titular role. Audiences were scared silly by the film, and its success went a long way towards legitimizing the horror genre in the eyes of both studios and critics, becoming the first horror film nominated for Best Picture.

Science Fiction – ‘Alien’ (1979)

A film that straddles both horror and science fiction on equal footing, Alien will take the latter category for its truckers-in-space aesthetic that brought a tactile quality to the genre that began with the lived-in production design of Star Wars but was plunged into full sweaty, dripping, steaming atmospherics with Ridley Scott‘s relentless classic. Alien‘s visuals are remarkable considering the relatively limited budget the film was produced on, but fans should thank all their lucky stars they got the film they did.

The clever conceit of an alien lifeform that gestates within a human host before bursting out of its chest was brought to biomechanical life through H.R. Giger‘s terrifying design and Carlo Rambaldi‘s physical build of the iconic head. It was then set loose in the incredible set work, with designs by Ron Cobb and art director Roger Christian. All these incredible craftspeople under Scott’s tight direction make Alien a singular visual sci-fi experience that puts it above the decade’s other masterpieces like Close Encounters of the Third Kind and Invasion of the Body Snatchers.

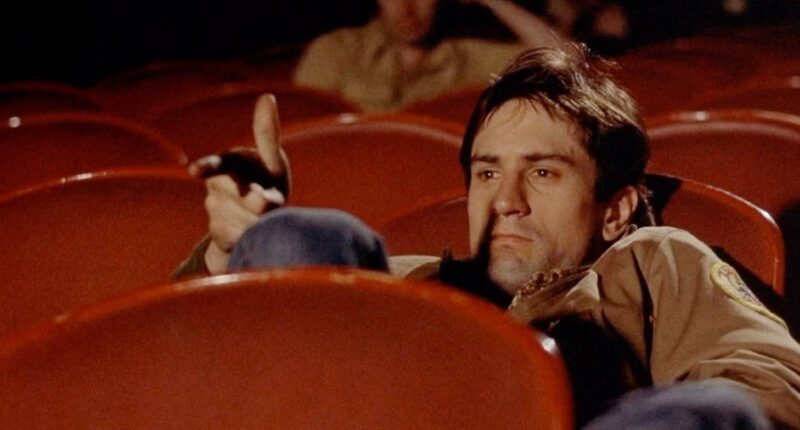

Thriller – ‘Taxi Driver’ (1976)

’70s thrillers cover a wide spectrum of subgenres, be it crime with Dog Day Afternoon, political with All the President’s Men, spy with Three Days of the Condor, or survival with Deliverance. They all deliver tense plots with characters living on the edge, but none plumb such disturbing psychological depths as Martin Scorsese‘s Taxi Driver. Written by Paul Schrader as a response to the general malaise that seemed to be affecting America at the time, the film is both a dark snapshot of the crime-afflicted city and a prophetic window into the psyche of a young, disaffected male. Robert De Niro‘s tightly coiled performance as taxi driver Travis Bickle is one of the best of the decade and his career, capturing the lonely soul of a man for whom violence is an inevitability.

The slow burn of Scorsese’s thriller makes it so that Travis’ target seems to constantly change. As he drops further into his silent rage against the city and its criminal elements, any of his passengers could become his first victim, or it could be Cybill Shepherd‘s Betsy, who initially seems charmed by his idiosyncrasies before seeing what lies beneath. The fact that Travis’ rage ultimately gets taken out on a scummy pimp and his predator clientele preying on Jodie Foster‘s Iris, an underage sex worker, is mere happenstance that only gets Travis branded as a hero, free to continue prowling the streets for his next target. It’s an unsettling ending to a dark thriller that personifies the pessimism that pervades so much of ’70s cinema.

Western – ‘McCabe & Mrs. Miller’ (1971)

Westerns were still quite prolific in the ’70s, with dozens of releases each year. The spaghetti Western continued in kind, while revisionist entries picked the genre apart. Sam Peckinpah continued the deconstruction of The Wild Bunch into his underrated films The Ballad of Cable Hogue and Pat Garrett and Billy the Kid, while Clint Eastwood got surreal with High Plains Drifter, and even John Wayne got reflective with the genre in The Shootist. If there’s one film that fully set about flipping the genre onto its belly, it was Robert Altman‘s self-proclaimed anti-Western McCabe & Mrs. Miller, which deliberately subverts the tropes of the genre, particularly with a final shootout that takes place out in the snow without any of the heroics or grace of the genre’s white-hat heroes.

Warren Beatty‘s McCabe is a bumbling and craven character who would just as soon hide in a chapel from would-be assassins than face them head-on. He’s a huckster and gambler who starts a brothel and gambling hall in a Washington boomtown alongside Julie Christie‘s madam, who also begins a transactional romance with him. This arrangement draws the attention of the typical mining company power players, who come into conflict with McCabe after he flails in his attempts to outmaneuver them, leading to the aforementioned snow gunfight. Featuring Altman’s characteristically loose narrative structure and layered dialogue, along with Vilmos Zsigmond‘s soft focus cinematography, McCabe & Mrs. Miller is one of the most unique Westerns ever made and the best of the ’70s.