Editor’s Note: The following contains spoilers for Alien: Romulus.

The Big Picture

-

Alien

stands apart from other science fiction films by delivering truly unique and believable extraterrestrial creatures that are not humanoid in form. - The costuming and performance of the actors behind the xenomorphs create a seamless work of art, hiding any aspect of the human inside and adding to their haunting appearance.

- The aliens in the Alien franchise have a deeper level of complexity, with a biomechanical aesthetic and a fully-developed biological cycle that taps into deep fears and anxieties about reproduction and motherhood.

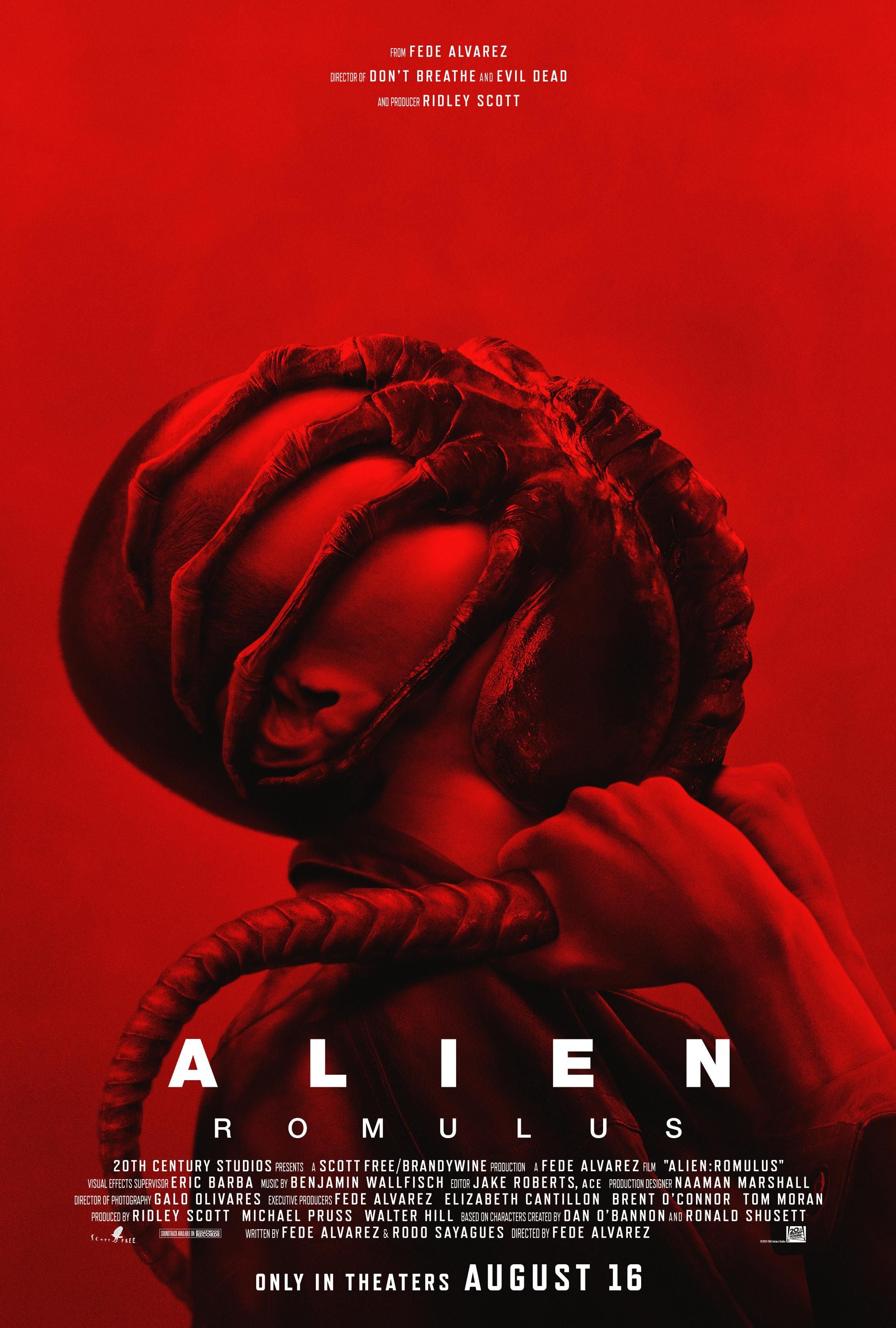

If there is one overall generalization that can be placed upon the science fiction genre of film, it’s that alien life forms are largely humanoid in form. Two arms, two legs, torso. Furry and short like Ewoks, furry and big like Wookiees. And if they’re not, they are a bastardization of Earth creatures à la Starship Troopers, or just kind of lame, like Star Trek’s troublesome Tribbles. Really, the only franchise that has ever truly delivered something believably not-of-this-world is Alien, a trend that continues with Alien: Romulus, in theaters now. No other franchise even comes close, a testament to the various means through which the films have brought face-huggers and xenomorphs to life. By utilizing and crafting a winning mix of the gifts of actors, practical effects, cinematography, and a healthy dose of artist H.R. Giger‘s nightmarish vision in creating these beasts, the Alien franchise has consistently delivered extraterrestrials that share little semblance of humanity, but lots of will to end it.

Movies Outside of Alien Have Failed to Match Its Creature Design

To truly appreciate just how far the Alien series goes above and beyond its peers, one has to realize just how truly homogenous intelligent extraterrestrials are in other films. Science fiction movies have visited planets from countless galaxies, but, somehow, bipeds are the dominant form of life. It doesn’t matter if the terrain on said planets would be better suited to limbless crawlers or multi-appendaged creatures. Regardless of atmosphere, these bipeds usually breathe the same way humans do. How they process the atmosphere might be different, but it doesn’t look all that different. Even in real life, the concept of aliens as being “little green men” with big heads and huge eyes is society’s go-to default. And they all speak English. Somehow.

Related

Where Does ‘Alien: Romulus’ Fit in the Franchise Timeline?

‘Romulus’ goes right between two absolute classics.

To a large degree, it makes perfect sense. Science fiction is one of the most costly genres of films, alongside fantasy and animation, at an average production cost of about $60 million. So, if a human actor can become a believable alien form through makeup or costuming, that becomes significantly cheaper than time-consuming practical effects to bring that form to life. The rise of CGI in creating extraterrestrials, too, is costly, maybe not as much as it once was, but still a significant investment in time and finances, and heavily reliant upon actors to interact with characters in their scenes that aren’t physically there. Some truly breathtaking aliens have graced the silver screen using these methods, but generally, they still look like a guy in a suit, or so obviously computer-generated that it takes the audience out of the film, even momentarily (Alien: Romulus is guilty of the same, but not for its use with the aliens, but rather with Ian Holm‘s appearance as an A/2). And this is where Alien begins to separate from the pack.

H.R. Giger Made Alien’s Xenomorphs Petrifying

A number of the xenomorphs in the Alien franchise are, also, guys in suits, but the costuming and the artist in the suit work together to create an actual creature, a seamless work of art where the humanity behind that haunting elongated head is lost. In Alien: Covenant, dancer Andrew Crawford played the lead alien, a man well known in the ballet and dance world as being able to eerily resemble a “specimen from another planet.” The actors behind the xenomorphs are purposely people with the ability to perform uncanny movements (much like Andy Serkis‘ Gollum, for example). The cinematography plays a part as well, cleverly capturing only brief sights of the creatures, with only the black sheen off of their heads to give their positioning away. They’re almost always in the dark, further hiding any aspect of the human inside, and when they aren’t, it’s typically in a close-up (that smile they give before they attack is creepy as all hell, but effective), or in quick cutaways, a montage as chaotic as the moment. Alien: Romulus has an excellent example of this, when dozens of face-huggers are inadvertently revived.

As for the look itself, you can thank renowned Swiss artist H.R. Giger. In preparing to film 1979’s Alien, director Ridley Scott came across Giger’s book Necronomicon, his first collection of the macabre, biomechanical works Giger is known for. One illustration, Necronom #4, captivated Scott so much that he asked Giger to design the xenomorph for the film, which turned into Giger working on the entire production design. As Scott recalls, “Down the line I realized it made a lot of sense for Giger to design everything that was to do with the alien. That includes the landscape and the spacecraft.” The costume for the alien uses real bones, a human skill at the tip of the alien head, and condoms for the lips, and when pulled together the effect is simply haunting, and with Giger behind the production design, the creature blends seamlessly into the world he’s created.

That commitment to the aesthetic is prevalent in Alien: Romulus, and it should come as no surprise. Director Fede Álvarez brought in the special effects team from Aliens to create the creatures for the new franchise entry. Álvarez was also deeply committed to using practical effects, with the team using animatronics and puppetry to bring the newest xenomorphs, face huggers, and a brand spanking new creature that appears in the final act, one that harkens back to the Newborn from Alien: Resurrection. Those practical effects throughout the franchise not only bring the otherworldly to life but add a visceral quality to the encounters between the protagonists and the creatures that can’t be replicated, no matter how realistic, by CGI. As Álvarez told The Hollywood Reporter, “It’s just whatever is best for the shot, and when it comes to face-to-face encounters and moments with creatures, nothing beats the real thing.”

There’s a Deeper Level to Alien’s Xenomorphs

There’s an even deeper level to the aliens in the Alien franchise that further separates them from others — a biomechanical aesthetic common to Giger’s works that further separates his aliens from the contenders. There’s actual thought placed into not only the xenomorph look but its biology too. There’s the acid for blood and the “extra” set of teeth that bring additional terror to a beast that’s already pretty damn frightening. The creatures look horrifying, but also have a beauty to them, with every part of their body covered in a black sheen that is both unsettling and mesmerizing. The life-cycle of the xenomorph, though, is especially telling of Giger and Scott’s commitment to deliver something unique. To put it simply, the life cycle of the xenomorph is a bastardization of human reproduction, a further allusion to the film’s sexual imagery.

The eggs have openings that originally looked very much like vaginas but were changed to a cross. As art director Roger Christian explains, “The first ones he did looked much more like a woman’s private parts, and the producers all worried,” Christian added. “Giger said, ‘Well, if it’s a cross, then it’s religious, and people don’t worry about that.'” The facehuggers that emerge look sperm-like, planting a seed into its host, which develops into the xenomorph that literally explodes from the chest cavity of the host (explored once again in all its glorious gore in Alien: Romulus). It plays into some of the deepest fears of humanity: Will my baby be a monster? Will there be problems during the pregnancy? What if I’m pregnant against my will? And what if my baby is a monster? (Also disturbingly touched on in the newest entry.)

The aliens of the Alien franchise succeed because they look otherworldly, and act otherworldly. They’re animalistic, yet intelligent, they’re dangerous, alive or dead, and they terrify on multiple levels. They come with a fully developed biological cycle, one that mimics the accepted norm but skews it in a manner that’s horrifying to even envision, let alone watch unfold on screen. These aren’t just humans painted green, told to come out on cue and spout gibberish about space treaties, or threaten galactic war if their demands are not met. The aliens of this franchise are fully realized, but with simple objectives: kill, and repopulate. Other science fiction franchises have aliens that kill, ones seeking to repopulate, and others simply looking to destroy whatever is in their path. But no other movie allows their extraterrestrial creature the depth that is afforded those in the Alien franchise, and until another steps up to the plate and does the same, it will continue to be the gold standard for aliens on film. As it has yet again with Alien: Romulus.

Alien: Romulus is playing in the U.S. at a theater near you.

Get Tickets