The first memory Nina Khrushcheva has of her grandfather is from a dinner party, when she was around four or five. He was hosting it at his dacha – a country house in rural Moscow – for the urban elite of 1960s Russia. There were world-famous poets and writers and theatre directors talking about politics, or, as Khrushcheva puts it, ‘boring adults having boring adult conversations. So I started slurping my chicken soup, loudly, until everyone stopped and looked at me. My mother was so, so angry. And my grandfather turns to me and says, “We are going to have a competition. You slurp, I slurp, and the person who slurps loudest wins. If I win, we all stop slurping, and if you win, everyone at the table will slurp.”’ Her grandfather won the challenge, and so the guests were spared.

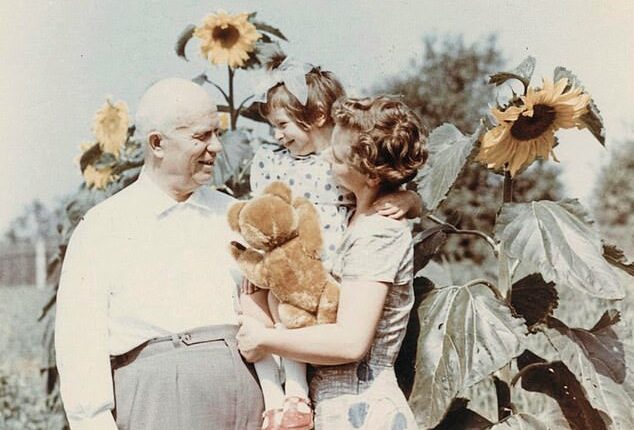

Khrushcheva’s memories of her ‘lovely, fantastic grandfather’ are, like this one, stereotypically warm. His insistence that she and her younger sister Ksenia help him plant vegetables in his garden was ‘torture’. While visiting him, she’d sneak into his office and bounce on his sofa to entertain herself because it had ‘the best springs’ and it would make her grandfather laugh. He was never strict and never told her to ‘sit up straight’ like her mother. Less stereotypical, however, is his identity: Nikita Khrushchev.

A quick recap for those whose social schedule leaves little time to listen to history podcasts: Khrushchev emerged as the premier of the Soviet Union in the power struggle that followed Stalin’s death in 1953, and was ousted, and culturally expunged, by rivals in 1964. His legacy is a confusing one. Seventy years ago this month he delivered the ‘Secret Speech’, which denounced Stalin’s purges, ushered in a less repressive era and closed the Gulag labour camps that killed around 1.6 million Russians. Eight months later, he sent Soviet soldiers to crush Hungary’s democratic uprising, killing around 4,000 people and displacing a quarter of a million.

Nina with her mother Yulia and grandfather Nikita Khrushchev, 1967

In 1962, his decision – explored by Khrushcheva and co-host Max Kennedy (the nephew of John F Kennedy) in the latest series of the BBC podcast The Bomb – to send atomic weapons to communist Cuba led to the Cuban Missile Crisis and, very nearly, global nuclear annihilation.

Of course, Khrushcheva, now 63, would not have understood any of this until much later. Not only because of familial bias, but because by the time she was two, her grandfather had been ‘eradicated’ from Soviet culture. When he was ousted, his rivals slated his ‘weakness’ on Cuba and ‘damaging’ reforms. But the Soviet system couldn’t admit to its people that leaders made mistakes or lost power, so the safest way to protect the myth of Communist infallibility was to quietly erase him from the story.

Khrushcheva was born in Moscow in 1962, to Yulia, Khrushchev’s adopted daughter (Yulia was actually his granddaughter, but her father, Leonid, died during the Second World War when she was two and her grandfather raised her as his own). The family’s time was split between Moscow and the rural dacha where Khrushchev lived out his forced retirement. The ‘disgraced’ family were much more comfortable than most: Khrushchev and his wife received a good pension (around 1,000 roubles, the same as a large factory owner), five staff, a chauffeured limousine and the special food and healthcare privileges reserved for the ruling class. Pretty cushy – except for the lurking KGB keeping tabs on the family’s movements.

Growing up, Khrushcheva’s favourite book was George Orwell’s 1984 because it captured the ‘doublespeak’ of her life. Moscow’s intellectuals, pleased by Khrushchev’s loosening of press restrictions, would visit the dacha for dinner, celebrating her grandfather as a ‘giant of politics’ and the ‘greatest hero’ of Russian history. Then Khrushcheva would go to her city school, open a history book, and her grandfather’s name wouldn’t appear. ‘He was deleted from the curriculum, newspapers, public records – everything. So, you know your grandfather is an important man, the country’s former leader… and then you go to school and he doesn’t exist.’

You’d imagine for Khrushchev, a man who talked about ‘burying’ his opponents, this disgrace would be unbearable. ‘My mother and my aunt would treat him like a china doll,’ Khruscheva says, ‘mourning for his lost position.’ But she is less sure. She thinks these years were perhaps the happiest of her grandfather’s life. ‘He was 70. He could write his own memoirs. He could take a car and go to the theatre. He could spend time with us. He could garden. Those final six years, they were happy.’

Nina Khrushcheva, granddaughter of Nikita Khrushchev

So for Khrushcheva – now Professor of International Affairs at The New School in New York City, and Khrushchev expert – was the plan always to become an academic and dispel some of these myths? Not quite, she says, with a distinctly Nikita-esque smirk. As a teenager, she wanted to be a clown and briefly went to circus school. ‘It was quite fun but didn’t last long.’ She was studying Russian Literature at Moscow University when Gorbachev opened Russia’s borders in the mid-80s and, like most 20-somethings, wanted to travel. All the best graduate schools were in America, so Khrushcheva – recently divorced after a very young, very short marriage – applied. ‘People were telling me, “You can’t do it,” but I was gutsy. I passed the tests and off I went.’ She hated New York for the first few hours because of the ‘skyscrapers and pollution’ but quickly acclimatised. Coming-of-age in Gorbachev’s laxer 1980s, Khrushcheva had grown up with American films and knew what to expect. The only real culture shock? ‘The American curriculum was so easy. I’d read all the required books and plenty more before I arrived.’

Khrushcheva is now a naturalised US citizen, which she says triggered national debate back in Russia. ‘In some places,’ she’s written previously, ‘school textbooks asked students whether it was right or wrong for Nina Khrushcheva to become an American’. Perhaps because of controversies like these, she’s unwilling to share anything about her family life. She was warm and affable when we spoke, but when I asked about children, I received a schoolteacher-sharp: ‘I will not speak about that.’

She has a PhD from Princeton, was a professor at Columbia University and regularly contributes to newspapers from The New York Times to The Wall Street Journal. It must be hard, I say, critiquing the, how to put it, divisive politics of her cuddly grandfather. ‘When people ask me about Khrushchev, I always say Khrushchev,’ she explains. ‘I very rarely say “my grandfather” when I’m talking about politics. In my work, he is a historical, not familial, figure.’

The distinction became particularly clear while recording the episode of The Bomb that covered the Cuban Missile Crisis, alongside Max Kennedy, nephew of John F Kennedy. ‘Max always says “my uncle”, “my family”,’ she says. ‘I almost never do that.’ Why? Partly because ‘it feels like bragging’, she explains, and partly because ‘when I talk politics, Khrushchev is separate from me. When I tell my own stories, he becomes my grandfather again.’

Khrushcheva is notably less nuanced when talking about modern Russia’s authoritarian leadership. She’s been one of the most vocal Russian-born intellectuals to denounce Vladimir Putin’s invasion of Ukraine, calling it ‘embarrassing’ and saying her grandfather would have found it ‘despicable’. Nonetheless she’s nostalgic for her childhood home: so much so she considered relocating permanently during Covid and visits Moscow ‘all the time’. ‘New York is my home,’ she says, ‘but Russia is my motherland. I’m a New Yorker, but I’m also, always, a Russian.’

All three seasons of The Bomb are available on BBC Sounds