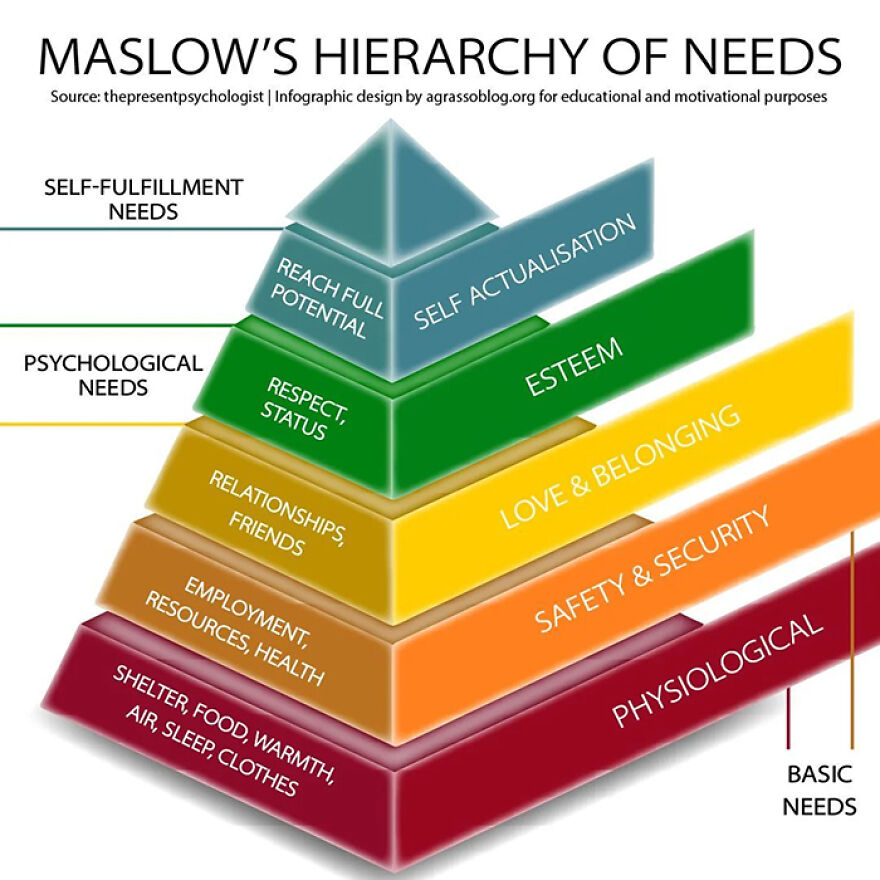

Abraham Maslow’s hierarchy of needs explores what drives human behavior, offering a popular framework for understanding motivation. Typically illustrated as a pyramid, the model organizes needs from basic survival to self-fulfillment.

It focuses on how humans prioritize different needs as they navigate life.

Image credits: Martin Barraud / Getty Images

But many critics argue the pyramid is flawed. While it claims that foundational needs like food and love must be met first, it ignores crucial variables. The model fails to account for extreme circumstances or cultural differences that shape how needs are experienced and prioritized.

Suggesting a fixed order oversimplifies the real complexity of human life.

The deeper we dig into the hierarchy, the clearer it becomes that it’s not a universal formula. Human motivation isn’t linear but more nuanced and deeply personal.

This article has been reviewed for accuracy and context by Dr. Sarah Meehan O’Callaghan, an interdisciplinary researcher whose work explores culture, gender, and psychology. Her expertise ensures the insights presented are well-grounded and credible.

How Maslow’s Pyramid Became the Standard Model

Maslow introduced his hierarchy of needs in 1943 through the paper “A Theory of Human Motivation” and later expanded it in his 1954 book “Motivation and Personality.”

The framework outlined five categories:

Image credits: @businessbrite / Instagram

Notably, Maslow never illustrated his theory as a pyramid. That visual came later, popularized by educators for its simplicity.

The pyramid quickly gained traction in classrooms and corporate trainings because it offered a tidy visual for understanding layered human motivations. But while the categories appear straightforward, how people prioritize them varies widely.

Cracks at the Foundation

Maslow’s hierarchy has been scrutinized extensively over the decades. A 1976 study by Wahba and Bridwell challenged its core assumption, finding little proof that people must satisfy lower-level needs before higher ones.

In practice, humans often juggle multiple needs simultaneously. Human Performance Technology notes that it’s difficult to measure how satisfied a need must be before another emerges or even to define what qualifies as a “need.”

“Studies that complicate Maslow’s hierarchy of needs are welcome critiques of oversimplifications of human motivation. Human pathology or desire, such as in cases of anorexia, would imply that motivation is not simply about meeting physical needs but that in many instances, humans can put those needs on hold to obtain another satisfaction,” says Dr. Sarah Meehan O’Callaghan.

Recent studies echo this critique, showing that safety and social connection can outweigh basic needs like food or water in certain crises.

For example, during hurricanes, earthquakes, or similar disasters, people often prioritize reuniting with loved ones or seeking shelter over eating or drinking.

Arxiv reports that disaster victims routinely delay evacuation to search for family, retrieve belongings, or follow crowds, and are driven more by emotion and connection than by base survival.

Image credits: @raisingchildren.net.au / Instagram

Overall, the research points to a more intricate picture of human motivation than Maslow’s model allows. Many alternative theories have stepped in to offer deeper explanations.

Belonging Over Bread?

Author and speaker Simon Sinek offers a pointed critique of Maslow’s hierarchy, arguing that the need for social connection may outweigh even our most basic physical needs.

He suggests that Maslow’s framework overemphasizes the individual, overlooking how deeply humans rely on their communities.

Image credits: @thejoshuablee / Instagram

In a conversation with Chris Williamson on the Modern Wisdom podcast, Sinek notes that some people take their own lives not from lack of food or shelter, but from an overwhelming sense of loneliness or hopelessness.

This, he argues, reveals just how fundamental our need for belonging truly is.

Maslow’s pyramid ranks social connection beneath physical survival, treating it as a secondary concern. But Sinek insists that being part of a group isn’t just about emotional fulfillment but staying alive.

He emphasizes that human beings are social animals, and that our well-being depends as much on community as on individual achievement.

Culture Clash With Collectivist Societies

Maslow’s hierarchy, rooted in Western ideals of individual achievement, doesn’t translate neatly across cultures. In collectivist regions such as East Asia and Sub-Saharan Africa, people often place the needs of their community or family above personal ambition.

In many cases, individuals define themselves through their social roles and relationships, valuing harmony over independence.

For example, rural communities in Sub-Saharan Africa frequently prioritize group welfare, even at the expense of individual comfort.

Image credits: @scmpnews / Instagram

Japan provides a striking example. The phenomenon of karoshi, death from overwork, reflects intense cultural pressure to serve the collective, even when it compromises health.

This dynamic challenges Maslow’s claim that basic physical needs must be met before social ones, suggesting that belonging can take precedence.

Non-Linear Needs in Crisis Zones

In disaster areas and conflict zones, Maslow’s model begins to unravel. When survival is at risk, people don’t always prioritize food and shelter first. Instead, many turn to meaning found in faith, art, or community to endure the chaos.

Even in extreme conditions, creativity thrives. Refugees have been known to write poetry, paint murals, or engage in religious practices to reclaim a sense of identity and hope.

Research consistently shows that spiritual and artistic outlets become vital lifelines during crises.

Viktor Frankl, who survived the Holocaust, captured this in “Man’s Search for Meaning.” He noted that many prisoners drew strength not from physical necessities, but from having a purpose, often by helping others.

His experience underscores how the need for meaning can rival or surpass basic survival.

Neuroscience Points to a Network, Not a Stack

Modern neuroscience pushes back on Maslow’s tiered model by showing that the brain doesn’t process needs in strict layers. Instead, systems responsible for basic survival, emotional connection, and reward are closely linked and influence each other constantly.

This overlap reveals how hunger and loneliness, for example, are not separate priorities but intertwined signals. Social needs are not luxuries but fundamental to staying alive.

Taken together, the research points to a model where physical, emotional, and social needs operate in tandem, not in sequence.

Competing Models That Fit Better

Several modern frameworks offer more flexible alternatives to Maslow’s hierarchy. One is Clayton Alderfer’s ERG theory, which groups human needs into three broad categories: Existence, Relatedness, and Growth.

Unlike Maslow’s model, ERG theory allows people to pursue these needs at the same time, adapting to their unique circumstances.

Another major alternative is Self-Determination Theory (SDT), created by psychologists Edward Deci and Richard Ryan. This model focuses on psychological needs that drive motivation: autonomy (the ability to direct one’s own life), competence (mastery of skills), and relatedness (connection with others).

SDT argues that these three needs are equally vital across all life stages.

Together, these models challenge the idea that motivation is a linear climb. Instead of a pyramid, they present motivation as a flexible system shaped by context, identity, and individual agency.

They suggest that we aren’t moving through a single pathway, but navigating a range of needs based on what life demands at any given moment.