Of course the nuance of exploring this historical phenomenon is one of the central points of the movie, but according to Wright, it’s also the nuance that scared Universal Pictures’ new management after the studio was merged with PolyGram Filmed Entertainment.

“There was a changing of the guard at the studio from the time that we shot the film until the time it was finished,” Wright explains. “And the new gatekeepers didn’t quite understand the film. I think they were scared. They were afraid of it and not quite understanding how it was, for example, that a Black man would find himself fighting on the side of the Confederacy, history be damned. There was a guy named John [Noland], and he was a scout for Quantrill, who of course we show on his famous raid into Lawrence, Kansas. So despite the historical accuracy and also the ways in which Ang framed it, they just couldn’t quite get their heads around it.”

The picture is actually quite slippery in its shift of perspective. Initially told from the POV of Maguire’s Roedel, the son of a German immigrant who is both too poor to own a slave and perhaps too ignorant to think of a reason to fight in a war beyond all his boyhood friends are doing it, the film slowly watches Roedel’s self-awareness grow after spending a winter hunkered down in a makeshift bunker with Holt. However, it also becomes about Holt’s own self-actualization, particularly as he outlives the man who ostensibly gave him freedom, as well as his sense of debt to white men who would kill others over simple ideas—ideas like teaching abolition in a new schoolhouse. It even finds space to puncture the mythology around what was then the emerging Western outlaw, represented by Jonathan Rhys Meyers as not-Jesse James.

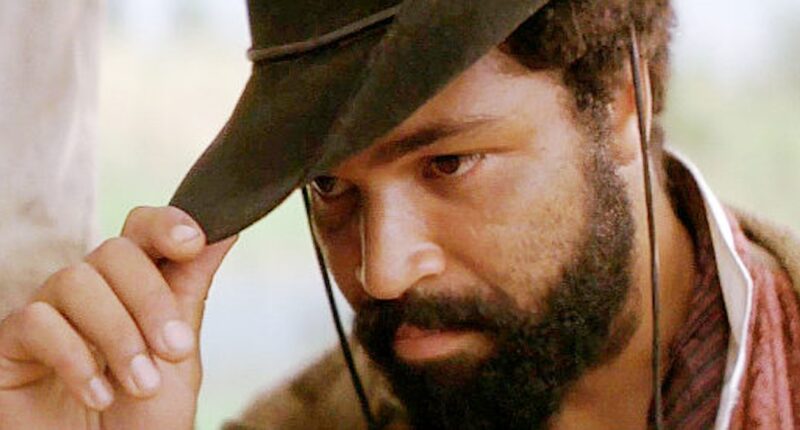

“For me what was exciting about that role was not that this was this freedman or soon-to-be-free man fighting for the Confederacy,” explains Wright. “For me what was interesting was that he was fighting for his own freedom and he was fighting to emancipate himself, as opposed to being emancipated by the Great White Northern Savior, which is what we very often see in cinema.”

He continues, “It’s one of my favorite experiences working on a film, and that had more to do [with us] riding horses every day for six months. It was just a joy. But it’s also a performance that I’m very proud of, and it’s one of the only films I think you’ll see in the entire canon in which a Black character rides off into the sunset at the end of a Civil War film.”

The movie indeed ends with Holt choosing to part ways with his friend on equal footing, and to also make sense of his own life as he rides off to discover what became of his family in Texas. The complexity of that ending also has echoes to this day, as many Americans continue to revise the realities of the Civil War, and perhaps a bit like some of the white characters in Ride with the Devil, shudder at their children being taught ideas in schools that make them uncomfortable.