However, in a bitter irony, Riley’s disappearance eventually evolved into its own internet mythology, feeding countless other YouTube videos and decades-later documentaries, including the one which begins Stuckmann’s film. At a glance, this documentary-within-a-movie is about Mia putting to rest Riley’s lingering mystery. That changes, though, once the cameras stop rolling and someone with valuable, missing DV tape shows up at Mia’s front door.

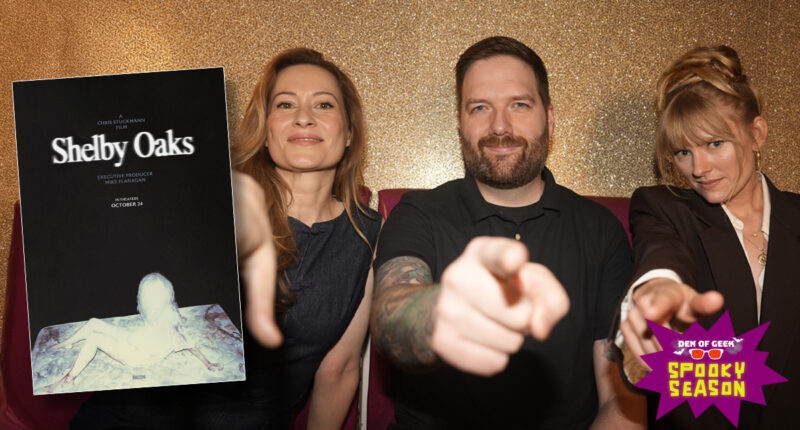

The impetus for the feature came out of Stuckmann’s own long-running YouTube channel dedicated to reviewing new releases, as well as vintage deep cuts often in the horror genre.

“I did a YouTube sketch with my wife in 2016, and we did this cabin in the woods thing where we went to a cabin in the woods and talked about cabin in the woods movies,” Stuckmann recalls with a slight smile. “Very original, I am a YouTuber. But we did this wrap-around sketch where this killer was trying to kill us, and we did it by ourselves and had so much fun doing it, and we were driving home from Tennessee—and it’s a six-hour drive—and we were asking, ‘Why aren’t we just making something? We are so tired of waiting.’”

Obviously from its premise about a YouTube personality going missing, the film touches on elements Stuckmann knows from his own life, right down to Riley disappearing at Shelby Oaks in 2008, which butts up against when Stuckmann launched his own channel in 2009.

Says the filmmaker, “I remember the quaint, charming days of early YouTube where there was just a few people who were talking about stuff on that platform. It felt super small and felt like this little community, so that was important to me.” Yet while the film started from a familiar place, one of the most striking things about Shelby Oaks is how it breaks free from preconceived notions of how a story about a missing filmmaker can play out. There are clear homages to found footage movies in Stuckmann’s debut, most notably The Blair Witch Project, yet after a mockumenatry-like first act, the film pivots hard into a traditional narrative structure with Mia turning off the camera.

“I remember the first time I was writing the treatment, it started as this sort of found footage, mocumentary/moc-doc approach,” Stuckmann explains, “and I thought to myself ‘what are the rules of this?’ And as soon as I started thinking in that way, I was upset with myself. Because I want to break some rules. You want to try and reinvent something and do something new, and I remember I called a filmmaking buddy of mine and asked, ‘Am I allowed to do this where it just changes?’ And he’s like, ‘Do whatever you want!’”