It happened in early December at a dinner party at a friend’s house near Sherborne in rural Dorset.

We’d had a glorious afternoon pootling along the Jurassic coast, walking our dogs on shingle beaches as the waves crashed dramatically, and exploring atmospheric Lyme Regis, where we walked on the pier and watched the low winter sun set over the English Channel.

We then headed back inland to the country home of one of my oldest friends for a long-anticipated supper party. My friend and her husband, me and mine, another old friend and hers, all well into our 50s, together for the first time in months. It was heaven. The host served a retro casserole from Delia Smith and there was blackberry trifle for pudding.

And then, shortly after we’d repaired from dining room to living room, glasses of fizz in hand, my right leg abruptly dislocated itself from my hip socket.

I went, in that instant, from feeling relaxed and blissfully happy to the depths of despair. Not only was I suddenly in searing pain, but I also immediately realised the torturous path that lay ahead of me.

You see, this had happened to me many times before. In fact, this was the sixth time the same hip had spontaneously dislocated in this way.

I had a full hip replacement in 2020. It dislocated three times before my original consultant at UCH in central London reattached the prosthetic hip with a new part – called a ‘revision’ – in 2024. Then that dislocated a further two times before I found myself in my current predicament.

And I knew, immediately and with catastrophic certainty, that the intense pain I was suffering now was going to be the defining feature of the days that lay ahead. You see, bitter experience has taught me that although medical staff have the ability to mute this pain to the point that it would be almost bearable, they do not do this.

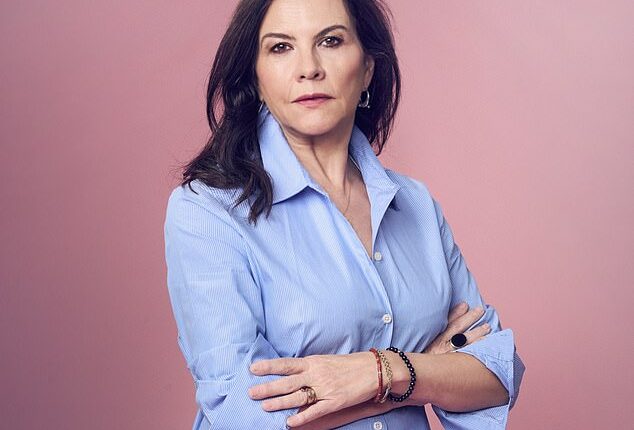

Sian Sturgis’ leg dislocated from her hip socket, leaving her in excruciating pain. But, she writes, the NHS has an issue with women’s pain, so her suffering was not treated with urgency

I knew with horrid certainty that I could look forward to a hotchpotch approach to pain management in the coming days; that I would be left for hours at a time to simply suffer.

I have learned the hard way that the NHS has a problem with pain. Especially women’s pain. It simply doesn’t treat it with the seriousness and urgency that it demands.

By the time I attended that Dorset dinner party, my hip had held good for almost 18 months, and I had started to allow myself to believe I was finally ‘cured’.

But now, bang, I was back to square one, looking at an emergency reattachment procedure followed by full surgery and all the horrifying but needless agony that both would see me subjected to.

The hours that followed still have the quality of a nightmare in my memory. Our lovely Saturday night became hellish.

I already knew that any movement meant instant suffering, so I spent the night lying as still as I possibly could on that sofa, sobbing, braced against pain and… waiting.

Finally, at around 5am, a paramedic crew turned up, dosed me up with morphine – ticking that box for now – and carried me out of the house into the waiting ambulance.

They took me to the nearest A&E – at Yeovil over the county border in Somerset – and within a few more hours, I was in theatre, under general anaesthetic. I can’t fault the speed or service of any of this.

But the news was not good. When I came round, feeling groggy and sore, the young consultant explained that she had managed to reattach my hip but wasn’t confident the joint would hold for long. She would discharge me but only on condition that I seek immediate referral to a specialist once home.

They took me out in a wheelchair. My husband drove into the ambulance bay and I was helped into the front seat, while our dogs in the back looked on quizzically. We drove the long way home in the dark, fearful of what lay ahead. I had already written off all our elaborate December plans – lunches and dinners, parties, tickets to the ballet, the theatre, a family meal for my oldest son’s birthday.

But even as I stepped slowly up the stairs to my bed, I could hear ominous clicks in my hip. I sensed – as would later be confirmed – that it wasn’t just unstable but had already become partially detached again. I was a ticking timebomb – and the pain was coming back in ever‑greater waves.

I knew that because of what doctors had taken to calling my ‘complex history’, I needed to be treated this time by the specialists at the Royal National Orthopaedic Hospital (RNOH). But for this I would need a referral – and 111 told me the only way of achieving this was to go back to A&E. Which meant another ambulance.

Sian, pictured in hospital, was taken to A&E for her pain but spent hours waiting before she was taken into the theatre and put under general anaesthetic

We called one first thing on Tuesday morning, and waited. After five hours a paramedic team came and decided the only way to get me downstairs was by dosing me with a lot of morphine.

I was beyond woozy when I made it into the ambulance, but when I got to A&E at Barnet Hospital it began to wear off.

What was the pain like? It’s hard to describe. It is so intense that it drowns out anything and everything else. It has the intensity and gathering fear of being on a rollercoaster – but one which doesn’t go anywhere.

It’s at once deep inside your bones but also in your stomach, your limbs, your brain – like a constant electric shock.

Often, people use the phrase ‘writhing in pain’ to describe what I was by then going through, but since any movement, no matter how small, sent shock waves through me, I wasn’t writhing but lying completely still – obsessively still – and calling for help that didn’t come.

Calling out made my body course with extra pain – but I was offered nothing stronger than paracetamol for many hours.

Finally, well into the evening, I was prescribed a cocktail of painkillers of the strongest kind – morphine, oxytocin and tramadol. At last, I thought.

This stuff doesn’t make you feel better, it just makes you feel less bad. It partially mutes the pain so that you can start to think about things other than the pain – or you would if the side-effects weren’t so mentally disorienting.

Rather than the dislocation itself, this is what I found so traumatising: the struggle over the following eight days on various hospital wards to get adequate painkillers.

The time at which the drugs were meant to be administered would come and go and nothing would happen. I’d buzz, I’d shout, I’d beg. But almost every time they were due, the nurses didn’t come – and I could feel the pain intensifying again.

On Thursday night I managed to get that transfer to the RNOH – but first I had to have a standoff with my care team at Barnet: I refused to move until my painkillers came. I knew the journey would be a nightmare of bumps without them.

This delayed things for hours. I lost track of exactly how many – four or five perhaps – but finally, well into the evening, my stubbornness won out, the pills came through and, after another ambulance trip across suburban north London, I found myself at the RNOH, a campus hospital in landscaped grounds.

I was given a large private room with views, as close as the NHS gets to five-star accommodation. But it didn’t give me any pleasure because the situation remained the same.

I had the best specialist care team in Britain discussing my treatment, but those running the ward were often hours late supplying my drugs. Again, I’d alternate between screaming for help and quietly sobbing.

Why did they keep failing on this issue? I feel sure it was partly because I was a woman, that there is a gender pain gap within the NHS which means women’s pain isn’t taken seriously.

Even years before my hip saga began, I had formed this impression. During two of my three children’s births – at Chase Farm in Enfield, north London and then UCH – there was ‘no anaesthetist available’.

I am small with narrow hips, but was forced to tough it out on gas and air. Of course, by the end that made no difference to the pain I felt – and both births were consequently traumatic.

And it’s been the same story with each of my hip displacements and their aftermath – at Pembury in Kent (the worst of them all – a disaster zone); at Barnet again; at North Middlesex; and at UCH, twice.

Sian was sailing from Portsmouth to Spain when she dislocated her hip on the ferry (pictured). She says this was the most traumatic episode, but the only time pain management was not an issue

Sian says one one occasion, she had to be strapped to a gurney while on morphine and ketamine to ease the pain

Sian is winched from a cruise liner in the Atlantic, before she made a terrifying 100-mile helicopter journey to a hospital in Bordeaux

In fact, the only time pain management was not an issue for me was during the most traumatic episode of them all – when, in August 2024, I dislocated my hip while on a Brittany Ferries boat between Portsmouth and the Spanish port of Santander.

On that very memorable occasion, I had to be strapped to a gurney while on morphine and ketamine, hoisted by ropes 40 ft into the air in high winds, on to a hovering Coast Guard helicopter, and flown 100 miles to a military hospital in Bordeaux.

And it was there, in France, that I had the only truly civilised care I have experienced during this whole sorry saga.

I spent six days in that Bordeaux hospital, starting with an attempted reattachment, then full surgery, and at no point was I left for even a minute in pain and unattended. They took the pain I was experiencing so seriously that I never once had to raise my voice or buzz forlornly.

Later I found myself wondering if it was because the place had begun as a facility for soldiers that they worked harder to keep my pain under control. Because I believe that essentially the pain of men is taken more seriously than women and treated with more alacrity.

Some may scoff at this, but so many women I’ve spoken to have had similar experiences and believe it to be true.

Since the Crimean War and the well-publicised intervention of Florence Nightingale, men’s pain has been seen as heroic and therefore deserving of urgent attention. Even if nowadays it’s more likely to be from sports or DIY than the battlefield.

But ‘women’s matters’ – and that includes my sorry hip – apparently aren’t as compelling to the medical profession.

One of the very worst things that happened during my run of horrific experiences was at Pembury hospital in Kent in 2023, when I was told I would not be treated unless I underwent a test to confirm I wasn’t pregnant. I was well into my 50s, on the other side of the menopause.

Had I had a baby at this point I would have been one of the oldest natural mothers in world history. But nevertheless they insisted: no pregnancy test, no treatment.

That test was among the most painful experiences of my life. They couldn’t move me so a nurse tried to catheterise me where I lay – which at that point was on a trolley in a corridor with people freely walking past. I would have been shocked at this were I not more preoccupied by screaming at each of her botched attempts to attach that catheter.

I think it took her five stabbing tries. To nobody’s surprise it then turned out I wasn’t pregnant.

Ever since I have had recurring UTIs which I’m sure began that day.

Would men be subjected to this kind of invasive indignity for no plausible reason? I don’t think so.

We still don’t know why my hip has gone wrong so many times. I had a first hip replacement to eliminate pain from arthritis, and that’s what seems to have set in motion this miserable chain of events. Events that to this day no one has been able to explain the cause of or provide any plan that’s guaranteed to stop them.

Because even now there’s no guarantee that it won’t happen again – in fact, I’ve been told the risk of recurrence is still as high as 20 per cent, and the upshot of that might well be a wheelchair.

I don’t think this is anyone’s fault, by the way. It’s simply my bad luck.

What I can’t forgive however is the sheer number of times, in so many different hospitals, under so many different NHS staff, that I have been left in agony when I simply didn’t need to be – all because of a lack of care.

That is what I find myself reliving in my nightmares.