“That the present situation i.e. the war is over between July the first and the 30th September 1943, the party of the first part M.T. presents the party of the second part with two bottles of Haig’s whisky.”

These words come from a handwritten agreement dated 3 March, 1943, penned by Ronald Joy, who entered into the pact as “the party of the second part” with fellow prisoner of war M. Thompson (“the party of the first part”) while both were imprisoned in a Japanese World War II camp located in present-day Shenyang, Liaoning province, in Northeast China, then occupied by invading Japanese forces.

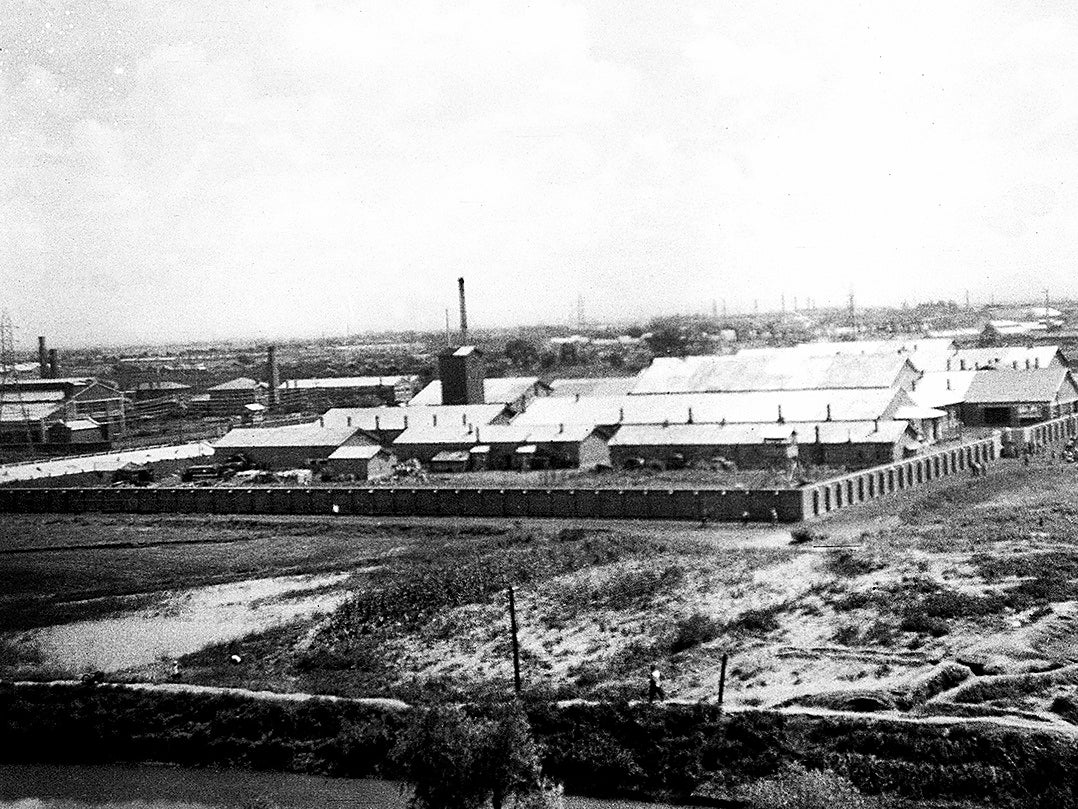

Known as the Mukden POW Camp — “Mukden” being the former name of Shenyang, or alternatively the Hoten Camp — the facility housed over 2,000 Allied prisoners, primarily Americans, British, and Australians, including the two men named above.

“When they made this agreement, they had been in the camp for less than four months and still held hope,” says Li Zhuoran, deputy director of the Shenyang WWII Allied Prisoners Camp Site Museum, which stands on the original site of the former Mukden Camp.

Yet, that hope wore thin, smoldered, and came perilously close to being extinguished by the prolonged war and the men’s drawn-out captivity, which lasted until August 1945. “Their time in the camp was marked by relentless physical, mental, and emotional trials,” Li continues, “as they endured every form of hardship — including the brutal winters of Northeast China, which claimed nearly 200 POW lives in the few months between late 1942 and early 1943, just before that agreement was made.”

Many of those who perished that bitter winter had already survived a gauntlet of horrors: the initial bombing of the Philippines — launched mere hours after Japan’s surprise attack on Pearl Harbour; the notorious Bataan Death March, where surrendering American and Filipino soldiers were forced to trudge over 62 miles through jungle heat and brutality, collapsing one by one along the way; and the harrowing journey aboard a Japanese “Hell Ship” — in this case, the Tottori Maru — so squalid and inhumane it earned the grim title of a “floating tomb” before delivering its emaciated captives to Busan, Korea, from where they boarded a train to Shenyang. (The British and Australian POWs of the camp mainly came from Singapore and Hong Kong.)

The Mukden Camp, as it came to be known, did not officially open until July 1943. Before that, prisoners were temporarily housed in disused army barracks. Spanning nearly 540,000 square feet and holding over 2,000 Allied prisoners, the Mukden Camp was the largest of Japan’s 115 POW camps across Asia during WWII. It also had two sub-camps located in Jilin province further north, where General Jonathan Wainwright and other high-ranking Allied officers were confined.

Today, the camp’s outer walls — once topped with barbed wire and watched over by guard towers — are long gone. Yet, a water tower and a tall chimney, once linked to the camp’s boiler room, still stand. In their shadow, a new building has been erected to display a miscellany of artefacts — mementos from days the POWs had desperately hoped would soon come to an end. These included personal effects like tin lunch boxes, cigarette holders and cases, and rather surprisingly, a gold tooth that once belonged to a POW.

Condemned to forced labour in factories that supported Japan’s military-industrial effort, some POWs secretly carved tobacco pipes from large chunks of wood as a subtle form of sabotage. Others engaged in riskier acts: According to former Mukden Camp prisoner Ralph Griffith, those assigned to the blueprint office deliberately inserted small errors into technical drawings, while others simply threw tools into the area to have concrete poured.

Some attempted to escape. On 23 June, 1943, three American POWs escaped from Mukden Camp but were recaptured and executed on 31 July. The youngest, Ferdinand Meringolo, was just 20 years old. Their escape was aided by Gao Dechun, a 19-year-old Chinese labourer at the factory where they worked, who risked his life to obtain a map of Northeast China. For his bravery, Gao was severely beaten and sentenced to 10 years in prison — a term terminated by Japan’s surrender on 15 August, 1945.