Hundreds of European ski slopes are lying abandoned in so-called ‘ghost resorts’ with more and more forced to close due to a lack of snow in recent years.

In France alone, 186 resorts that once saw reliable snowfall have shut while an increasing number of low-level ski areas are battling to make ends meet amid dwindling downfalls.

The start of the 2025-26 ski season has been no exception with social media videos showing poor snow coverage in parts of France, Austria and Switzerland.

Patches of grass, rock and dirt can be seen on typically-snow-covered slopes in some of Europe’s winter sports meccas including in the Northern French Alps and Austria’s Tyrol region with skiers are having to head to high altitude slopes to seek out the best conditions.

While heavy snow has fallen in the Pyrenees and at some Italian resorts in recent days, videos from France and Austria have shown skiers sliding on thin tongues of icy slush and riding on ski lifts over near naked slopes.

Resorts across the continent continue to battle unseasonably high temperatures that pose an existential threat to slopes at lower altitudes – and have already put many out of business.

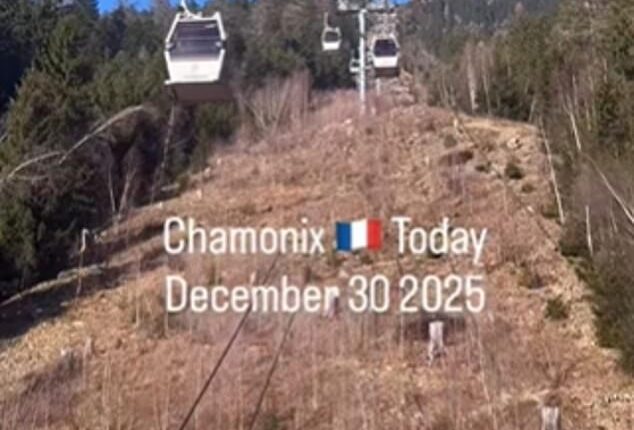

This pictured shows a barren slope at Chamonix ski resort on December 30, 2025

A video taken in Chamonix shows skiers sliding on thin tongues of icy slush

Last month Urs Lehmann, the CEO of the International Ski and Snowboard Federation warned that melting glaciers and shrinking snow could have a devastating impact on winter sports.

‘The ripple effect of climate change on every aspect of society is truly terrifying,’ he said during an event held on Switzerland’s Great Aletsch Glacier.

‘It turns out that the realm of snow sports — not only at a competitive level, but for all the communities that revolve around ski resorts — is among the first to experience this devastating impact directly,’ Mr Lehmann added.

A 2023 report warned that over half of Europe’s ski resorts will face a severe lack of snow if temperatures rise 2 degrees Celsius above pre-industrial levels, while nearly all would be affected by an increase of 4 degrees – presenting challenges for the tourism industry, and threatening a harsher reality for ski lovers.

In the paper in the journal Nature Climate Change, experts warned that a common solution — production of artificial snow – would only partially offset the decline and would involve processes like snow blowers that generate more of the same greenhouse gases that are heating up the globe in the first place.

Repeated and increasing wintertime thaws have saddled many European ski resorts in recent years, leaving many slopes worryingly bare of snow.

Along with glacier melt, snow shortages have become a visible emblem of the effects of climate change.

Everything from basic tourism to pro ski competitions have felt the effects.

Tourists ski along a poorly snow-covered access slope leading back to the low-altitude resort of Leysin, through a snowless surrounding landscape on December 27, 2025

Patches of grass, rock and dirt can be seen on typically-snow-covered slopes in some of Europe’s skiing meccas. Pictured: A slope with no snow at an Austrian ski resort in December 2025

Skiers ride on a ski lift over near naked slopes in La Clusaz, France

A snowboarder sits in a chair lift above a snowless landscape in La Clusaz resort near Annecy, southeastern France, on December 20,2025

As snowfall becomes more and more unpredictable across Europe’s top skiing destinations, conversations are now being raised over the future and state of these landscapes. Pictured: A skier slips down a poorly snow-covered access slope in the resort of Leysin on December 27, 2025

In France alone, 186 ski resorts have been permanently shut in recent years and there are 113 ski lifts totalling nearly 40 miles in length that have been abandoned.

The closure of Céüze 2000 ski resort at the end of the season in 2018 came as a shock for local residents, and the structures of the popular destination – which was once known for its dramatic white Alpine landscape – have now been left to rot.

As snowfall becomes more and more unpredictable across Europe’s top skiing destinations, conversations are now being raised over the future and state of these landscapes.

The Mountain Wilderness association estimates that there are more than 3,000 abandoned structures scattered around French mountains, slowly degrading Europe’s breathtaking terrain.

Over in Italy, some 90 per cent of the country’s pistes now rely on artificial snow to ensure even distribution, according to data from Italian Green lobby Legambiente.

But transforming water into snow calls for temperatures close to zero degrees.

Meanwhile, around 70 per cent of pistes in Austria rely on artificial snow to keep pistes accessible, as well as 50 per cent in Switzerland and 39 per cent in France.

It comes after fights broke out between skiers in the Dolomites earlier this month after a lack of snow due to warm weather shut several runs creating massive queues at lift stations.

Pictured: A ski lift at the former resort Céüze 2000 ski resort in France in January 2023. It was forced to close due to a lack of snowfall

The chaos ensued just weeks before Italy is set to host the Winter Olympics in Milan and Cortina d-Ampezzo in the Alps.

Temperatures hovering just above freezing, combined with weeks of dry weather, have severely limited snow cover across the Dolomites, located in northeastern Italy.

Artificial snow-making offered little relief, as conditions were too warm for machines to operate effectively, leaving pistes to turn muddy.

This is one of several setbacks, with Olympic organisers admitting this week that they had a ‘technical problem’ with the production of artificial snow due to problems with the water supply.

The issue affected a site in Livigno in the Alps where freestyle skiing and snowboard events will be hosted.

Video footage from the Dolomites shows tightly crammed skiers pushing, shoving and looking angry as a crowd gathered near the connecting lift between Marmolada and the Sellaronda circuit.

On social media, skiers shared photos and videos showing vast crowds packed tightly in front of the lift stations.

Queues were particularly severe at the connecting slope leading to Arabba, which had been closed because of insufficient snow.

Skiers attempting to return were left reliant on a single chairlift, which normally carries six people uphill but had been reduced to just three seats for the descent.

According to il Dolomiti, the resulting congestion led to waiting times of up to 45 minutes.