Farmers across the US are struggling after Donald Trump suddenly froze billions of dollars in federal grants awarded under Joe Biden.

Hundreds of small family farms fear they won’t get reimbursed for new, cleaner irrigation equipment or solar panels they bought with the promise of a rebate.

Others have delayed improvements like fencing, expanded grazing areas, and other projects at a critical time as the snow and front begin to thaw.

Crops could die or be eaten by pests, animals could perish or not be used as efficiently, and small operators with tight profit margins are in financial trouble.

Many of these farms supply grocery stores and wholesalers to restaurants, which could face shortages in some areas.

Hugh Lassen and his wife and two teenagers grow organic, wild blueberries on their Intervale Farm in Cherryville, Maine.

Last year they bought solar panels to run their home, a blueberry sorter and 14 freezers. They did it thinking they’d get an $8,000 grant through the Rural Energy for America Program.

‘It´s never the right time to spend $25,700,’ Lassen said. ‘It’s a huge amount of money for us because we´re pretty small… you also have college expenses looming.’

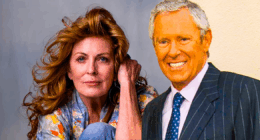

Organic wild blueberry farmers Hugh and Jenny Lassen pose in their home in Cherryfield, Maine

Organic wild blueberry farmers Hugh and Jenny Lassen can jars of blueberry spread at their home

Trump ordered a freeze on giving out these funds, but federal judges said departments can disburse them.

Yet many departments have not resumed writing checks, so questions remain for some business owners who spent years making plans for improvements they could afford only with grants.

‘We’ll just have to suck it up if somehow the funding doesn´t come through,’ Lassen said.

REAP, offered through the US Department of Agriculture, is one of the many initiatives rocked by the funding freeze.

It provides grants to small businesses in rural areas so they can generate clean energy or improve their energy efficiency.

Besides solar, it has helped fund wind turbines, electric irrigation pumps to replace diesel ones, and corn ethanol.

Once a business gets approved for REAP, it purchases the technology and operates it for at least 30 days.

Then a USDA agent comes out personally for verification and barring any problem, the check gets issued. Some people have spent months on their applications.

Deanna and Christopher Boettcher run Mar Vista Farm and Cottages in Gualala, California, and began their REAP application in 2023.

They put in time going over plans with contractors and filling out paperwork for 48 solar panels to cover about 80 per cent of their electricity needs.

Solar panels on a workshop roof catch the sunlight at Intervale Farm

The home of organic wild blueberry farmers Hugh and Jenny Lassen

The day they received approval to buy the panels, the funding freeze was announced.

‘I am speechless,’ Deanna Boettcher said. ‘Absolutely this will change my plans. There is no way we can build the solar system without the funds… So many obstacles and hurdles they put in the way, and to finally get there and then this.’

Their solar system cost $82,600. REAP is supposed to cover half. ‘We´re not going to even think about starting it unless we know that it´s not frozen… so we´re back to where I was two years ago.’

Lassen stressed that lower energy costs make farm products cheaper to make, allowing them to be priced lower.

Solar and wind are appealing to remote communities because they can be cheaper than traditional energy sources, such as diesel generators and irrigation pumps.

Grants have proven to be a major driver of new clean energy projects in rural areas because they lower the price tag.

Ang Roell, a farmer and beekeeper in Massachusetts, is waiting on a frozen grant for $30,000 to build deer-proof fencing, mulch, and an irrigation system for a new orchard.

Without the fencing, deer will eat the saplings of chestnut trees and elderberry bushes they planted, and the crop will be ruined.

Ang Roell, a farmer and beekeeper in Massachusetts, is waiting on a frozen grant for $30,000 to build deer-proof fencing, mulch, and an irrigation system for a new orchard

Brian Geier (pictured with his wife Elizabeth Tobey), a farmer in Indiana, was promised $10,000 from the Agriculture Department to expand his sheep grazing fields

And without the irrigation system, he will struggle to keep other crops regularly watered, and they may die too.

‘We risk losing the plants because we can’t keep up with the watering schedule. The delay of time might not seem like a big deal for someone who is not a farmer. But it actually is,’ they told NBC.

Roell decided to plant the orchard after Hurricane Helene destroyed many of the beehives, and wanted the business to be more resilient.

‘We are able to have a diversified farm that has other products to offer and can offset losses when catastrophes like this happen. But instead, now, we have the federal government as a catastrophe,’ they said.

Brian Geier, a farmer in Indiana, was promised $10,000 from the Agriculture Department to expand his sheep grazing fields.

Expecting the money to come in, he bought lambs from a local breeder that he now has no money to pay for when they are born in nine weeks.

‘Farmers have to shift when timelines change. We have to adapt given the biological situations going on with animals and the seasons,’ he said.

Vanessa Garcia Polanco, government relations director for the National Young Farmers Coalition, an advocacy group for farmers and ranchers, said there was a riple effect within the sector and beyond.

‘With this uncertainty, they are pulling out of farmers markets, canceling contracts already because they do not think they will have the capacity to meet them,’ she said.

‘When all that funding is frozen, it sends a signal to them that their business plan is not safe.’

Geier in his field that he planned to improve for sheep grazing

Expecting the money to come in, he bought lambs from a local breeder that he now has no money to pay for when they are born in nine weeks

Much of the Trump Administration’s opposition to the funding, particularly for solar technology and environmental efficiency, is ideological.

Trump has spoken often about his support for oil and gas, erasing environmental and climate policies created under the Biden administration.

His key advisor, billionaire Elon Musk, has said the government should scrap all federal tax credits and subsidies.

Russell Vought, the newly confirmed White House budget director, co-authored the conservative agenda for Trump’s second term, Project 2025, which criticized renewables like wind and solar and encouraged more oil and gas usage.

USDA leaders ‘have been directed to assess whether grants, loans, contracts, and other disbursements align with the new administration’s policies’, according to a statement from the department.

It noted last week that Brooke Rollins, secretary nominee, ‘will have the opportunity to review the programs and work with the White House to make determinations as quickly as possible’, once she’s confirmed.

Rollins, after she was confirmed earlier this week, didn’t offer any good news in her first statements on the matter.

‘It is clear that some of this funding went to programs that had nothing to do with agriculture — that is why we are still reviewing,’ she said on Thursday.

She blamed, without any evidence, the Biden administration’s ‘disastrous policies of over-regulation, extreme environmental programs, and crippling inflation’.

The Lassens’ solar system has a Tesla inverter, which converts direct current from the panels to the alternating current used on the property.

A pot of wild blueberries cooks on a woodstove at Intervale Farm

A wild blueberry plant protrudes from the snowpack at Intervale Farm

Hugh said this puts him in a ‘funny place where we´re benefitting from the brainpower,’ but could also suffer from Elon Musk´s ‘slash and burn cost-cutting’ efforts.

‘Farmers and small business owners throughout Appalachia and rural America are struggling to stay afloat,’ said Chelsea Barnes, director of government affairs and strategy at Appalachian Voices, a nonprofit focused on sustainability.

‘For people who have been awarded REAP funding and made purchases but haven’t been reimbursed, ‘that will cause significant financial harm’.

REAP originated with the 2002 Farm Bill and has long enjoyed strong bipartisan support for energy self-reliance, with money flowing in via farm bill legislation and the Inflation Reduction Act.

The program has spent $2.4 billion total since it was created and about half of that came from the Biden administration IRA, passed in 2022.

‘It’s really counterproductive to go after a program that does so much to help farmers bring down their costs,’ Andy Olsen, a senior policy advocate at the Environmental Law and Policy Center, said.

‘This is something that everybody agrees on. It primarily benefits Republican districts.’