The Thirteen Colonies didn’t have a unified culture at the outset of the American Revolution, so that means a Muslim immigrant is just as American as someone whose ancestors have been here for 400 years. America has never had a common cultural heritage, and you’re an evil right-wing bigot if you think it did, at least according to a recent article in The New York Times.

The author of the article, Leighton Woodhouse, conveniently spells it out in his headline: “The Right-Wing Myth of American Heritage.” His evidence for this so-called myth? Some Irish Presbyterians and English Quakers had a disagreement in colonial Pennsylvania and called each other bad names in a pamphlet war.

According to Woodhouse, “This was the state of relations between European settlers on the brink of the American Revolution. It’s a history that is inconvenient to the latest ideological project of the nativist right.”

True Americans, proponents of this emerging patriotic mythology believe, are the cultural descendants of founders who were united by a shared system of values and folkways even more than by an Enlightenment political creed of equality, liberty and democracy. Those founders were Protestant, largely English-speaking, Northwestern Europeans. Those who can trace their bloodlines to that group, which one essay describes as a ‘founding ethnicity,’ are, in some spiritual sense, deemed more American than those who cannot. And the dilution of that pure American stock by mass immigration has made the country less culturally unified.

“But the mythology these conservatives are spinning is historically delusional. Americans have never been ‘a group of people with a shared history.’”

This entire argument is, of course, nothing but leftist propaganda trying to convince you that bringing in Third World migrants who have no cultural affinity for American values and have no desire to assimilate is just part of the great American experiment.

“The United States isn’t exceptional because of our common cultural heritage; we’re exceptional because we’ve been able to cohere despite faiths, traditions and languages that set us apart, and sometimes against one another,” Woodhouse writes later in the article. “The founding fathers were an assortment of people from different histories and backgrounds who coexisted — often just barely — because they didn’t have any other choice but to do so.”

The author tortures the definition of “common culture” to be as wide or narrow as he needs it to be to push his agenda. Apparently, Irish Presbyterians and English Quakers were so different that they were at each others’ throats and it’s a miracle they were able to cohere into a nation, but having Protestant Europeans, Catholic Latinos, Hindu Indians, and Muslim Arabs in the same country is a recipe for a melting pot utopia.

Suggesting that the differences between Irish Presbyterians and English Quakers are comparable to the differences between Protestant Americans and Somali Muslims is, frankly, absurd. Different denominations and nationalities had their squabbles in colonial America, no doubt, but it’s also undeniably true that Protestant Europeans are the ones who forged this nation out of untamed wilderness and therefore have a claim to the title Heritage American.

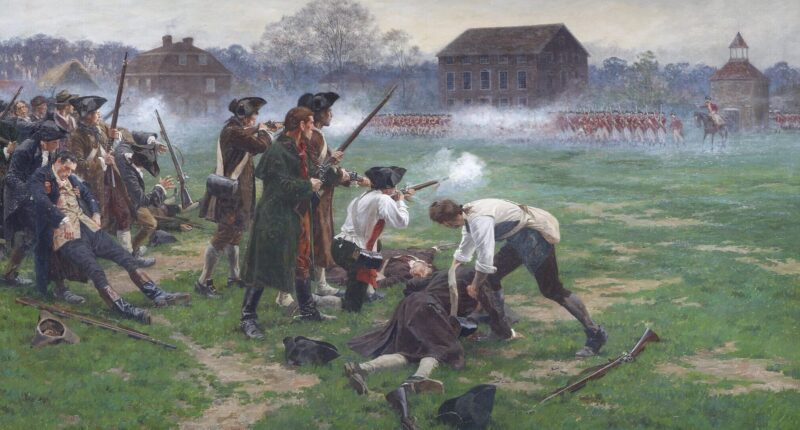

All humans throughout all of time have had squabbles with their neighbors over small differences in doctrine or custom, but that doesn’t negate the fact that groups of people can form a coherent shared culture. Despite their differences, the majority of settlers of the Thirteen Colonies had enough foundational similarities to nonetheless create a cohesive nation: a common religion (Protestantism in particular and Christianity more broadly), a common language (English), and a belief in natural rights.

Those who came after were assimilated into that existing American culture. Woodhouse notes that some minority groups in the colonies fretted about losing their cultural identity: “Lutherans fretted about replenishing their stock of German-speaking ministers, lest their children be lost to vulgar English ways.”

But he neglects the fact that they did assimilate. Those German Lutherans learned English. They successfully integrated with the English majority. It helped that they already belonged to the common religion, Christianity, and that they had a shared history in Europe.

The line “Americans have never been ‘a group of people with a shared history’” might just be the most bald-faced lie in a piece that seems to revel in them. The colonies believed they had enough in common to band together against the tyranny of the British Crown. Even before the Revolution, Benjamin Franklin proposed the Albany Plan of Union in 1754, which called for a united colonial government that would administer all of the colonies.

In the antebellum period, Americans believed there was such a thing as a Heritage American. They were obsessed with the events and principles of the founding, and they were immensely proud of their republican heritage.

Every political movement in pre-Civil War America, from the Know Nothings to the abolitionists, draped itself in the notion of Heritage America and the responsibility of being the heirs of the founding generation. The North and the South differed on the issue of slavery, and the regions had unique customs, but they both acknowledged their shared history as Americans.

Acknowledging that Heritage Americans exist and that there is a Heritage America reminds us that this country was founded by a particular group of people who had concrete religious and cultural ties that allowed them to bind together a nation. It also reminds us that those ties are currently under attack from the far left and can be lost.

Columns like the one Woodhouse wrote represent the ongoing decades-long effort by the left to diminish the significance and character of the founding and to launder the idea that the American people are interchangeable (and therefore replaceable) with any other people. If there’s no significance to the people who founded the nation and their descendants, then nothing is lost if they’re replaced.

The people who settled and first built this nation do indeed deserve more reverence than those who came later and reaped the benefits of the mores and institutions those settlers established. Remembering the particular cultural heritage of the founding keeps us anchored in a uniquely American identity — one the left is desperate to destroy.

Hayden Daniel is a staff editor at The Federalist. He previously worked as an editor at The Daily Wire and as deputy editor/opinion editor at The Daily Caller. He received his B.A. in European History from Washington and Lee University with minors in Philosophy and Classics. Follow him on Twitter at @HaydenWDaniel